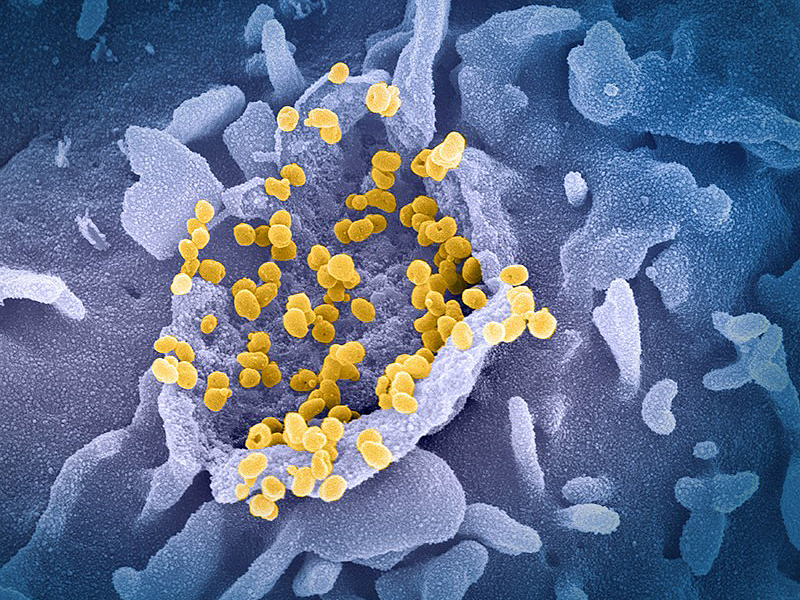

He cites: “Protection is relatively short-lived” temper nature Jeffrey Townsend, co-author of the study, a bioinformatics researcher at Yale University School of Medicine in Connecticut, who and his team studied the long-term protection of those who have experienced COVID-19. “We need to be vaccinated even in case of infection,” he said when presenting the results of the research, as the results showed that the protection obtained in this way is not very durable.

Additional data will be needed in the coming months and years to figure out how long it takes to file natural immunity, but now a typical account for estimating persistence of SARS-CoV-2 immunity suggests that antibody levels from previous infections may strongly influence the risk of re-infection, but it is not a long-term solution.

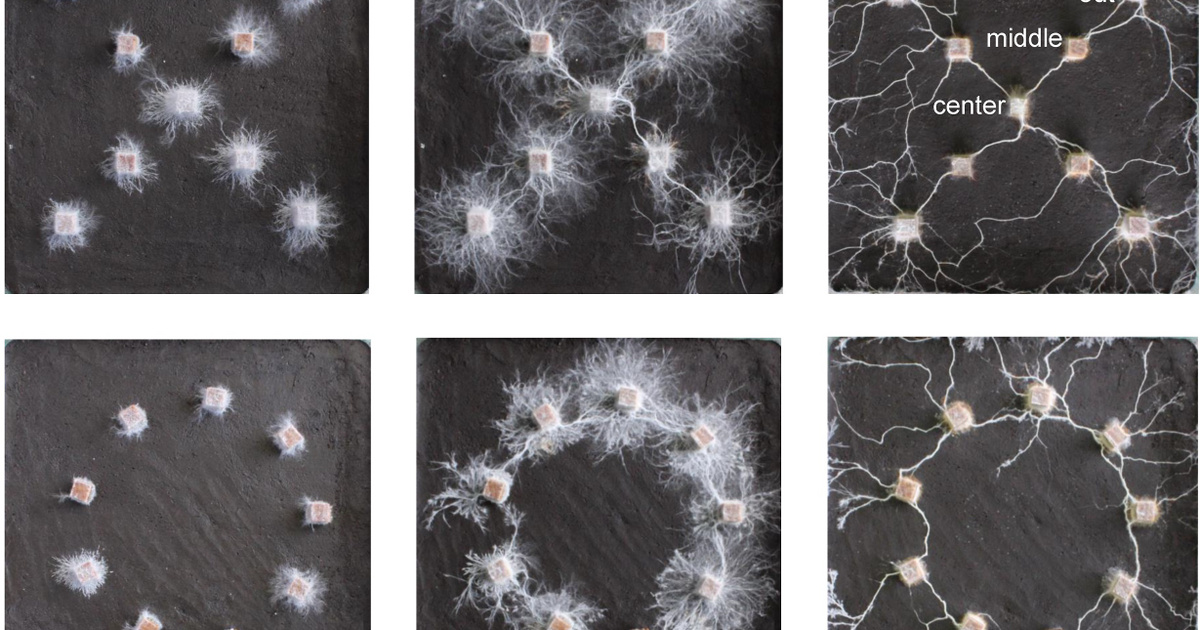

Data from a previous study allowed the research team to model this effect years ago for “endemic”, that is, constantly circulating cold-causing coronaviruses. However, SARS-CoV-2 is too new to provide such long-term data, but by modeling statistical data collected on the basis of specific rhinoviruses, estimates can already be made.

In doing so, the scientists combined genetic data from SARS-CoV-2 and three endemic coronaviruses and pathogens closely related to SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV to create a virtual virus family tree. The authors then used this tree to model how the characteristics of viruses evolve over time. Taken together, these characteristics provided an estimate of the decrease in antibody levels following SARS-CoV-2 infection causing the current epidemic, as well as other factors needed to understand the risks of re-infection.

The results show that the average risk of re-infection increases dramatically from about 5 percent four months after the initial infection, and then rises to 50 percent after 17 months. In general, the natural protection appears to last less than half that of the three cold-causing coronaviruses.

Townsend says he is “surprised and frightened” by his findings, which suggest that Covid-19 is likely to turn from epidemic to endemic, but that no real natural protection against it is being developed. He stressed that there are still many unknown factors remaining, including the potential risk of a disease in the future if someone becomes infected again. The response of individuals can vary greatly in both susceptibility to re-infection and the course of disease in the event of re-infection. But the emergence of a new strain of the virus – now prevalent – could also be a variable factor The delta version, for example, is more contagiousof indigenous wildlife. The result, then, is that it is not worth playing for innate immunity.

Sarah Kobe, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Illinois at Chicago, cautions that the new research is based on the assumption that the genetic similarity of viruses predicts similarity of traits important for re-infection. He points out that it may be too early to make a confident statement about how quickly protection declines after infection with SARS-CoV-2. He adds, however, that according to science, protection is already declining: “No one would expect immunity to last long for a virus that specifically evolves to avoid the development of immunity.”

Kobe also points out that infected people need to boost their protection with a vaccine. The study looked at people who received Covid-19 in 2020, some of whom were re-infected in May or June 2021. It was found that those who did not receive the vaccine were twice as likely to become infected during this period than those who received both the virus and the vaccine. The current estimate, based on this research and comparison with similar viruses, highlights the fact that the novel coronavirus may be with us long before the pandemic is over.