When it comes to environmental and climate protection, landscaping automatically appears to be a good solution, but this is not always a good decision – as the article on mta.hu explains. Peter Türk, head of the Lendület Functional Group and Environmental Research in Restoration, warns that instead of afforestation, we are doing more to protect the local grasslands.

When a forest is planted on arable land left deserted in Western Europe with indigenous species, most places revert to the state that naturally developed there before civilization advanced. When there was a good chance a forest existed 6-8000 years ago, the conditions were right for the newly planted forest to survive and sequester carbon in the tree trunks.

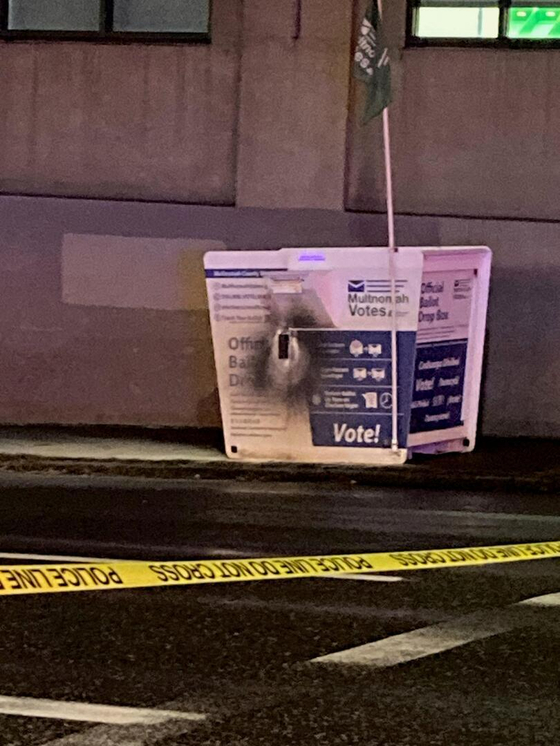

Photo: Alexandra Beer/Getty Images Hungary

However, the situation is often not clear: since arable land is not worth turning into a forest, if decision-makers look for suitable areas, they often look to grasslands.

However, the vast majority of researchers in the recovery environment say that this is not a good solution. First, pastures are able to sequester a lot of soil carbon. When the climate does not allow for the development of forests – and arable land in Central and Eastern Europe is often created by breaking up such areas – the real good carbon sinks are grasslands. Anyone trying to plant trees or create tree farms here will be worse off in the long run than if they keep the lawn, because under these conditions the farms will need to water and replenish nutrients regularly, which means very high maintenance costs.

Afforestation can initially be a resounding success, particularly with fast-growing exotics with optimal nutrients and water supplies, such as the now-fashionable emperor hybrids—but at a great cost.

Fast-growing tree species deplete the soil’s water resources, and in the absence of replenishment, the groundwater level quickly begins to decrease, which is already a current problem in many places: the groundwater table between the Danube and Tisza has fallen several meters to the bottom.

The shadow of tree plantations is beginning to destroy the grass of the bushes, and the processes of decomposition, that is, the release of carbon dioxide, will soon reign in the soil as well. After a few years, a decade or so, the trees begin to dry out, forcing the farmer to harvest the entire stock and go back to the lawn, while the entire tree farm was a source of carbon dioxide rather than sequestration.

Peter Turok and colleagues environmental restorationTherefore, we invite the scientific community, civil society activists, decision-makers and “Plant a tree!” Replace the logo with: “Restore the natural vegetation!”.

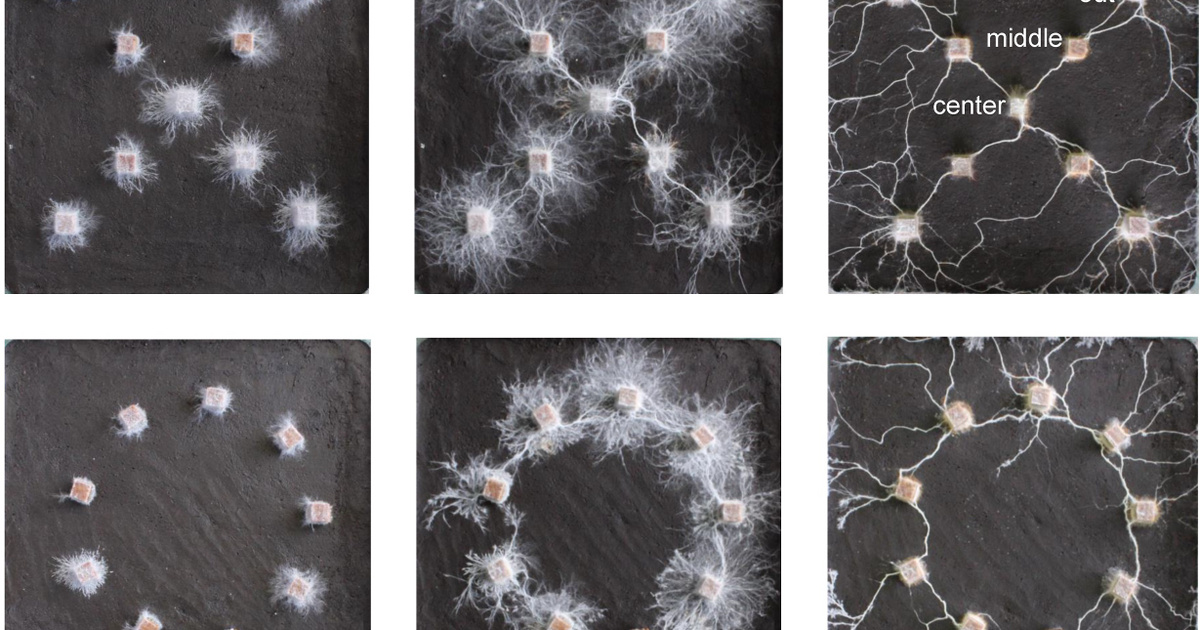

The researchers will suggest expanding the possibilities of tree-planting campaigns and believe that nature should simply be allowed to lead the way.

(MTA)