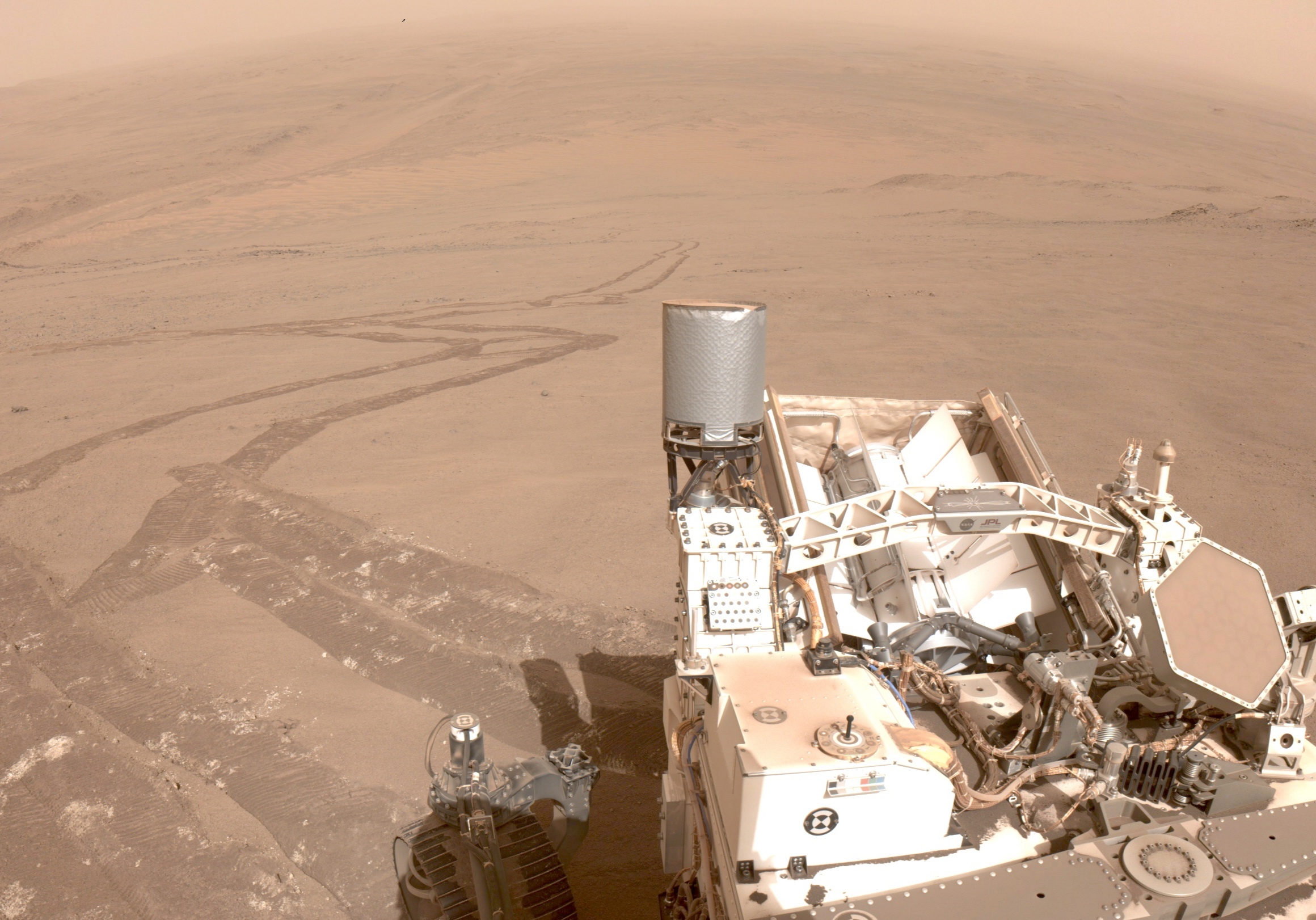

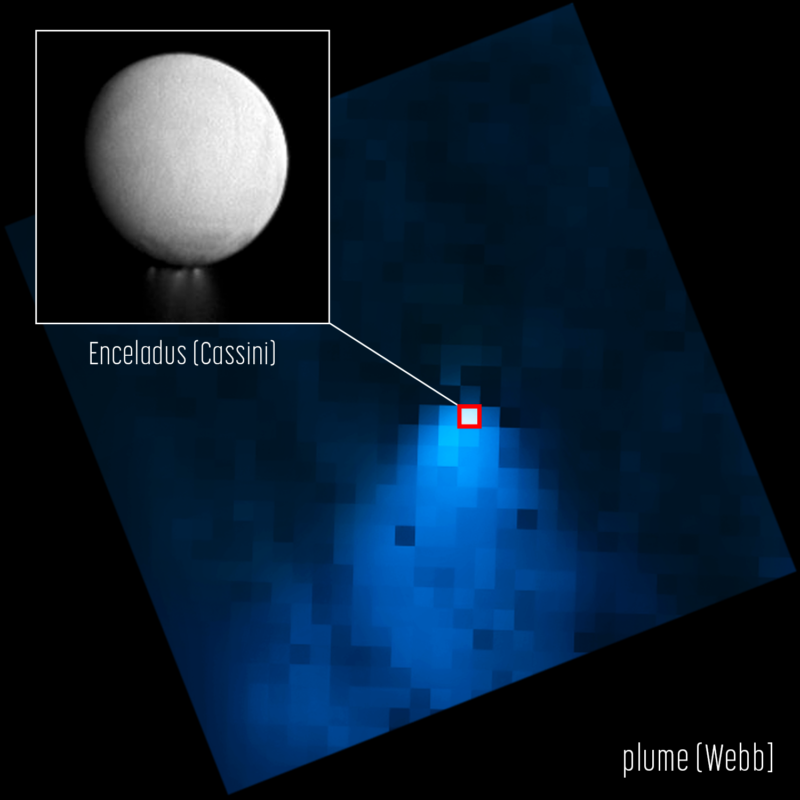

Enceladus, the frozen moon orbiting Saturn, has caught scientists’ attention because of water vapor escaping from its icy crust, potential evidence of a subsurface ocean. And the ocean means that it has the potential for life (at least life as we know it). Now, NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has detected an unprecedented plume.

Water vapor from Enceladus is trapped by cryogenic volcanoes that form over cracks in the ice. These plumes can extend hundreds of miles from the surface. When a team of NASA researchers took a closer look at the new JWST data, they discovered that one plume near the moon’s south pole was much larger than any other. At over 9,500 kilometers (6,000 miles) in diameter, it is the largest water spray ever seen in space. It is 20 times the size of Enceladus itself and extends far enough to easily cover the distance between Los Angeles and Buenos Aires. As Enceladus continued to orbit Saturn, this plume of water vapor formed an eerie halo around the planet.

“This is the level [water] The activity identifies … Enceladus as the main source of water in the Saturnian system. stable It has been accepted for publication in Nature Astronomy.

construction rings

The halo (or ring) that Enceladus leaves behind actually creates most of Saturn’s electron ring, the largest outer ring. Although Enceladus has been suspected to be geologically active since Voyagers visited Saturn, NASA researchers first confirmed the existence of the hot springs in 2005 by analyzing data from the Cassini spacecraft and Herschel Observatory. In 2019, additional Cassini observations showed that the e-ring formed from this. It is fueled largely by water vapor escaping from Enceladus, which explains why this ring appears fainter and fainter than others.

Cassini’s spacecraft and mass spectrometer have also found water vapor in Saturn’s rings and other moons. Webb added to Cassini’s legacy by providing a broader picture of the Saturn system. It now provides unprecedented insight into how water vapor from these emissions contributes to the torus and water supply for Saturn and its rings.

Webb’s instruments were able to see that most water droplets from normal Enceladus vapor do not remain in the torus near the moon. Its 33-hour orbit – just 1.37 Earth days – means it spreads water vapor widely around Saturn. It does it especially fast, with Mega Bloom spraying an astonishing 300 liters (79 gallons) per second. Webb’s returned observations show that only about 30 percent of this water remained in the rings, while 70 percent was dispersed throughout the Saturnian system. This means that Enceladus supplies the system with most of its water.

What’s in the water?

Webb made his observations using an integrated field unit (IFU), which can image an object and see the spectra it emits, which tell us what material the object is made of. The IFU is part of the Webb Near Infrared Spectroscopy Instrument (NIRSpec), which can see molecular emission across a wide range of the infrared spectrum. Infrared radiation emitted from the plume showed not only that it consisted of water vapor, but also how far the water vapor extended off the surface and showed its enormous size.

The NIRSpec data was also examined for organic molecules such as carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, methane, ethane, and methanol, which may be potential indicators of life or vital processes. There was no trace of this organic material in the column.

The researchers also said so stable.

Although there is no organic matter in the supergiant, Enceladus’ vapor plumes are thought to originate from hydrothermal vents in the depths of the subsurface ocean. These formations are also found at the bottom of Earth’s seas, where hot water heated by subterranean magma flows into the frigid ocean. Enceladus’ core produces enough heat to keep water liquid.

Perhaps one day, another volcanic eruption captured by Webb might signal life in the hidden world of ecology. Enceladus was already vaporizing water It has been found to contain organic compounds It could react chemically to produce amino acids, the building blocks of life on Earth, and one day we may see other potential signs of life.

Elizabeth Wren Irish. His work has appeared in SYFY WIRE, Space.com, Live Science, Grunge, Den of Geek, and Forbidden Futures. When not writing, he shapeshifts, draws, or disguises himself as a character no one has ever heard of. Follow him on Twitter: @hravenrayne.

List image you created NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, and G. Villanueva