With Hungary taking over Slovakia in 2019 with moderate inflation, general government deficits and the balance of payments and overtaking Poland in per capita GDP, there is relatively little room to criticize Orbán’s government’s economic policy, writes Kenja Keneres, business director for Századvég Gazdaságkutató Zrt. Vice.

In addition, real wages have risen steadily since 2012, household consumption spending has risen steadily since 2013, and unemployment was at a record low until 2019. We do not see exactly what the restrictions imposed on some of the actors in the economy caused last year. , We only know:

The crisis struck Hungary at a time when its economy was on a stable basis.

Of course, the poor is the poorest type of economic argument most important in periods when relative prosperity, even as a result of an external shock, is followed by a downturn.

The criticism also fuels popular belief, but in the case of Hungary, the poorest are excluded from rapid growth, as they have no chance of riding the bullet train.

However, in this regard, the last focus is on the fact that the relative income distribution has not changed significantly in the last ten years (2010-2019), that is, the scissors between the poorest and the richest have not moved, are not accurately drawn and are not satisfactorily detailed. Portrait of Hungarian Society.

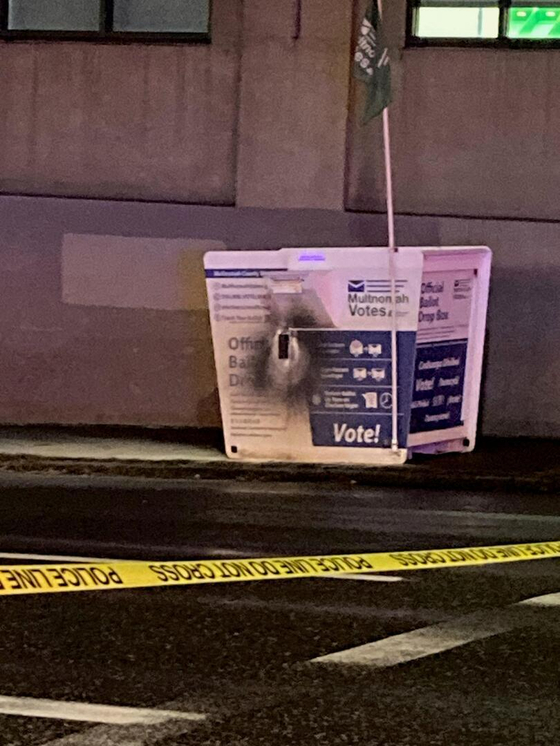

Photo: Shutterstock

The same data meant that the poor were able to get the share of expansion in equal measure as the rich, meaning that the increase in the performance of the economy was felt everywhere, even in the lower classes.

The wave raised every ship.

We can get a more accurate picture if we also take into account the figures of civil society organizations and the Statistical Office of the European Communities on deprivation: in the last decade, the percentage of people living in severe material deprivation in Hungary has decreased more than the average of the European Union, by two-thirds. Compared to 2010, the number of people in major difficulties with unexpected expenses decreased by more than 4 million.

Indicators that aggregate income distribution, including the Gini coefficient, are inappropriate for measuring poverty – based on the fact that the United States or Germany are worse off than Hungary, where the concentration of income is higher than here. The only indicator presented in the European Union appears to be more appropriate for this: the proportion at risk of poverty or social exclusion. In addition to making the position of individual member states comparable, the Common European Index examines three aspects of poverty that are common indicators of income deprivation in social policy.

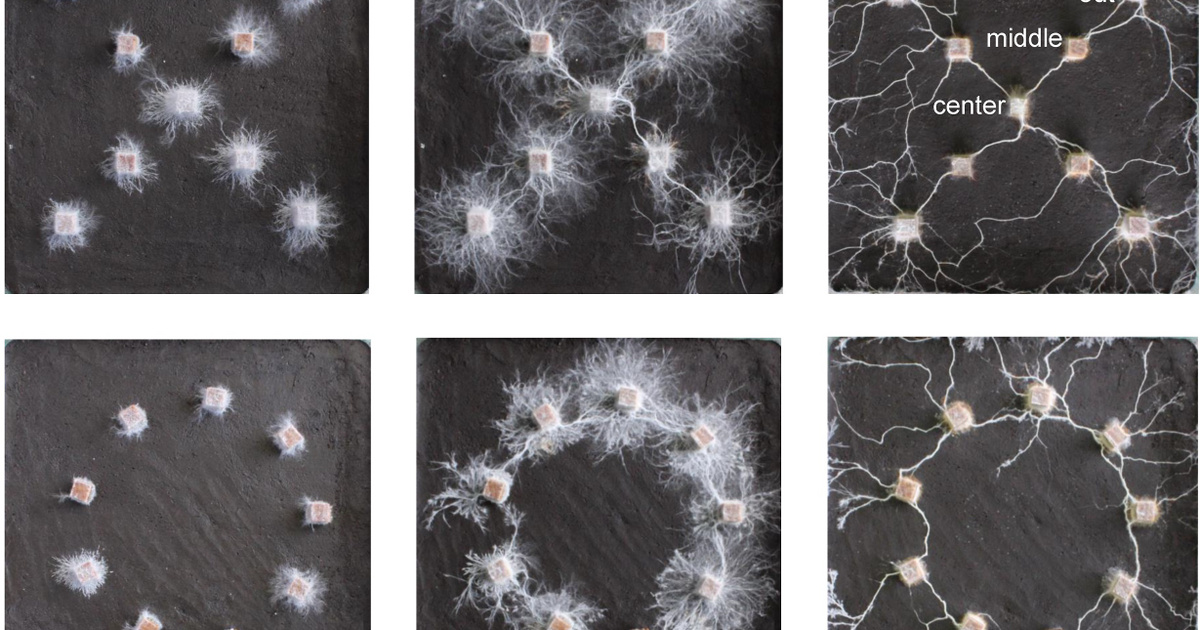

Percentage of the poor in each category in Hungary Photo: End of the Century / Central Statistical Office

- The first is relative income poverty, which means net income is less than 60 percent of the average.

- The other is the proportion of people in extreme material deprivation, which includes those who will have to give up at least 4 of the nine specified consumption items for financial reasons.

- The third is extremely low work intensity: Those who live in homes where working-age family members spend less than a fifth of their potential work time.

In Hungary, one in three people was at risk of poverty or exclusion in 2010, but their proportion had fallen to 17.7 percent in ten years – by 2019 – according to data from civil society organizations.

Severe financial deprivation (arrears related to loan or housing repayment, insufficient heating of the apartment, lack of coverage for unexpected expenses, low consumption of meat or fish or equivalent nutrients every two days, no one-week vacation away from home, no car For financial reasons, financially, it does not have a washing machine for some reason, does not have color TV for financial reasons and does not have a phone for financial reasons).

Exposure to poverty risk Image: End of the Century / Eurostat

The proportion of households with very low labor intensity decreased from 9.7% to 3.6% in nine years due to employment growth, while relative income poverty decreased from 14.1% to 12.2%. Here we see that income conditions are thus becoming more balanced and the proportion of those earning well below the average is smaller. The latter is also the result of a significant increase in the minimum wage.

Hungary also performs well in international comparisons in terms of poverty indicators (here we can compare 2018 data). The poverty risk exposure was much higher than the European Union average in 2010, but fell below the European Union average by 12 percentage points in 2018 (while the index improved somewhat across the European Union).

Basically, there are two processes that have contributed significantly to poverty reduction in the past ten years: on the one hand, increased employment, and on the other hand, increased wages. The role of increased employment is also prominent because many people, in this way, were given wages, i.e. higher income, instead of assistance, and thus had a better chance of getting out of poverty. The increase in the real value of the minimum wage by about two thirds during the period under review played a major role in this. Continuing these processes and recovering from the damage caused by the Coronavirus can further reduce poverty levels.