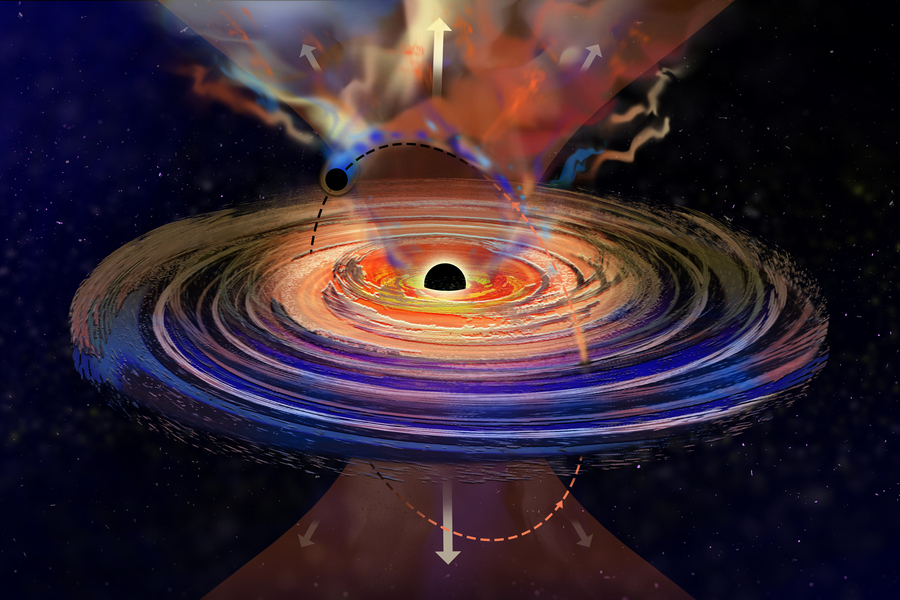

A team of astronomers has discovered that a previously quiet black hole at the center of a galaxy about 800 million light-years away has suddenly erupted and is spewing out plumes of gas every 8.5 days. We have never seen such periodic hiccups in black holes. According to experts, the explosions can be explained by another, smaller black hole orbiting the central supermassive black hole.

Researchers in the journal Science Advances It has been reported About the results. Their theory calls into question our traditional view of the accretion disk of black holes, according to which a relatively uniform disk of gas orbits around black holes. The new results suggest that accretion disks may have a different composition and contain more black holes or even stars.

The research group worked with data from the system of 20 robotic telescopes of the ASAS-SN network. Some of the network's telescopes are located at different points in the northern and southern hemispheres. They scan the entire sky once a day looking for supernovas and other transient phenomena. In December 2020, the telescope network detected an explosion in a galaxy about 800 million light-years away. The approximately 1,000 times brightness was observed by Dhiraj Basham, lead author of the study. He decided to use NASA's NICER X-ray telescope to study the event. He was fortunate that the end of the one-year period during which he had the opportunity to use the telescope was approaching.

Basham set up NICER to monitor the eruption for about four months. During this period, the instrument recorded the X-ray emission from the distant galaxy every day. Analyzing the data, the researcher noticed an interesting pattern: during the four-month eruption, he detected a slight decrease in brightness in a very narrow band of the X-ray band, which followed each other every 8.5 days.

The recorded signal was similar to what we see when a planet passes in front of its star and briefly obscures part of its surface. However, no star is capable of blocking the light of an entire galaxy.

While searching for an explanation for this phenomenon, he came across a recent study written by Czech theoretical physicists. According to the research paper, it is theoretically possible for the galaxy's central supermassive black hole to host another, much smaller black hole. The smaller object might rotate at a different angle from the accretion disk of the larger black hole, passing through it at regular intervals like a bee through a cloud of pollen. The magnetic fields prevailing on both sides of the black hole push away the cloud that settles during the passage. Every time the smaller black hole passes through the disk, we see a plume of gas. If the gas column moves toward our line of sight, we find that the brightness of the galaxy decreases, as if something were blocking it at regular intervals.

“I found this theory very interesting. I immediately wrote to them that we had observed exactly what their theory predicted,” Basham said.

In collaboration with Czech specialists, he carried out simulations of NICER observations. The results supported the theory that the observed explosion could be caused by another, smaller black hole orbiting a central black hole and regularly penetrating its disk.

The galaxy was relatively quiet before December 2020. The mass of the central supermassive black hole is estimated at 50 million solar masses. Before the explosion, it had a faint, diffuse accretion disk, and the smaller black hole of 100-10,000 solar masses orbited in relative obscurity.

According to the researchers, in December 2020, a third object – perhaps a star – approached the system and was torn apart by the gravity of the supermassive black hole: a phenomenon astronomers call a tidal catastrophe. The stellar material being pulled out suddenly briefly illuminated the black hole's accretion disk, which spiraled down toward the monster. The black hole consumed the star's debris for four months while the smaller black hole continued to orbit it. As it passed through the disk, it released a much larger plume of gas than before, which was then detected by NICER.

The researchers also ran several simulations of uniform brightness drops. According to the results, it is a kind of David and Goliath system, where a smaller, intermediate-mass black hole orbits its supermassive companion.

“This is a great example of how debris from an exploding star can be used to illuminate the core of a galaxy that would otherwise remain dark. It's like looking for a leak in a tube of fluorescent paint.” – said Madrid astronomer Richard Saxton, who was not involved in the research. “The results show that galactic cores can often contain supermassive binary black holes, an exciting development for future studies of gravitational waves.”

source: What

comment