“Now you eat instead of two” – this popular “wisdom” ranks high in the already long list of annoying comments for pregnant women. Although this myth is far from the truth, there is no doubt that pregnancy is an energy-intensive activity.

According to the results of new research conducted by Sciences Published in a journal conducted by researchers from Australia's Monash University, the actual energy demand is much greater than scientists previously thought: 50,000 calories during the nine months of pregnancy. (The energy content of a food is actually measured in calories, but in common parlance this is shortened to kilocalories.)

Previously, the energy demand during pregnancy was estimated to be much lower, as it was assumed that most of the additional energy used for fetal growth accumulates in the fetus itself, which is relatively small. But Australian evolutionary biologists have found that only 4% of the energy needed for pregnancy is incorporated into the fetus, and 96% of it is used by the mother's body.

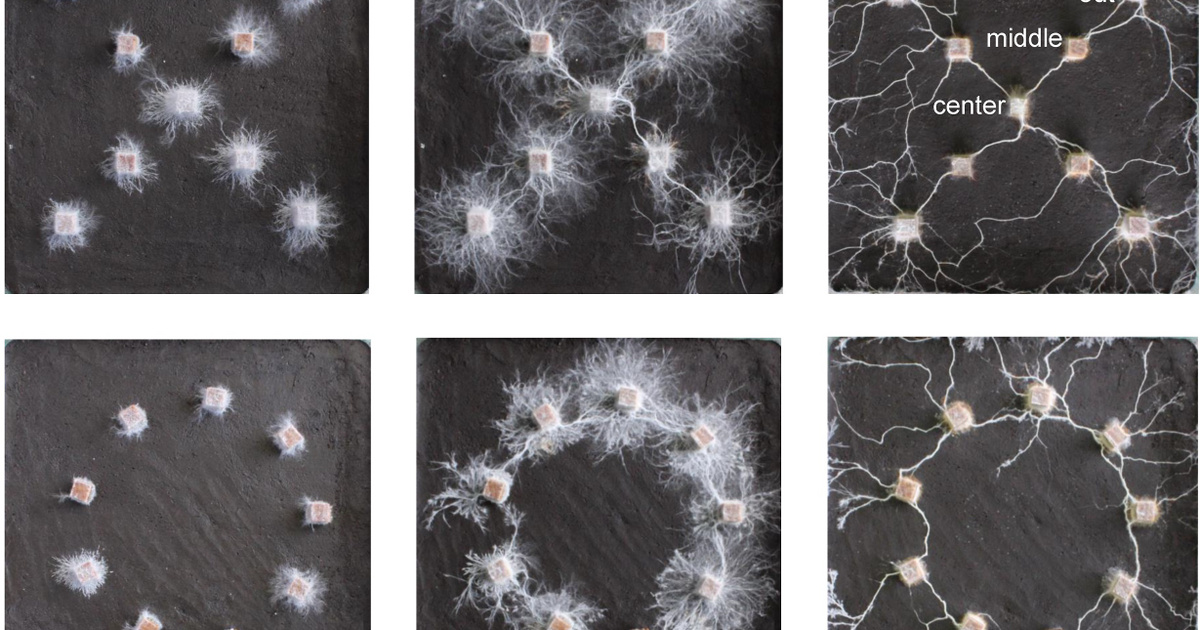

Researchers have estimated the energy required for pregnancy in more than eighty animal species. To do this, they compared the metabolic rate of pregnant and non-pregnant females (which can be estimated, for example, from oxygen consumption), and then subtracted the energy content of the fetus from the energy surplus. In this way, they obtained the excess energy requirements of the pregnant female's body.

The basic laws emerging from the results are perhaps not so surprising, as it has been found, for example, that the larger the animal, the more energy is required to produce offspring. Warm-blooded animals (constant body temperature) consume much more energy than cold-blooded animals, because they are constantly expending energy to maintain their body temperature (which is why cold-blooded snakes can survive for weeks without food).

Surprisingly, mammals spend almost an insignificant part of the energy used for pregnancy purposes (ten percent on average) on the growth of the fetal body. This indirect energy cost is partly used in the formation of the placenta and the delivery of food to the fetus. In humans, the indirect costs of pregnancy are particularly high (96 percent), because pregnancy in humans takes a particularly long time.

The enormous expenditure of energy by mammals during pregnancy explains why, after the birth of their offspring, mothers usually care for their young for a particularly long time. They put so much energy into pregnancy that if the offspring died, much of the resources invested in the project would be wasted.