As a regional representative of a common household insecticide, Gregor Samsa might have been mystified by the situation if he had encountered a life dominated by giant insects typical of the era in the primeval forests of Europe sometime between 345 and 290 million years ago. A meter-long dragonfly would dart nearby, while Arthropleura, an armored dinosaur measuring 2.5 meters long and half a meter wide, which could grow to 45 kilograms, walked in front of the famous hero's feet.

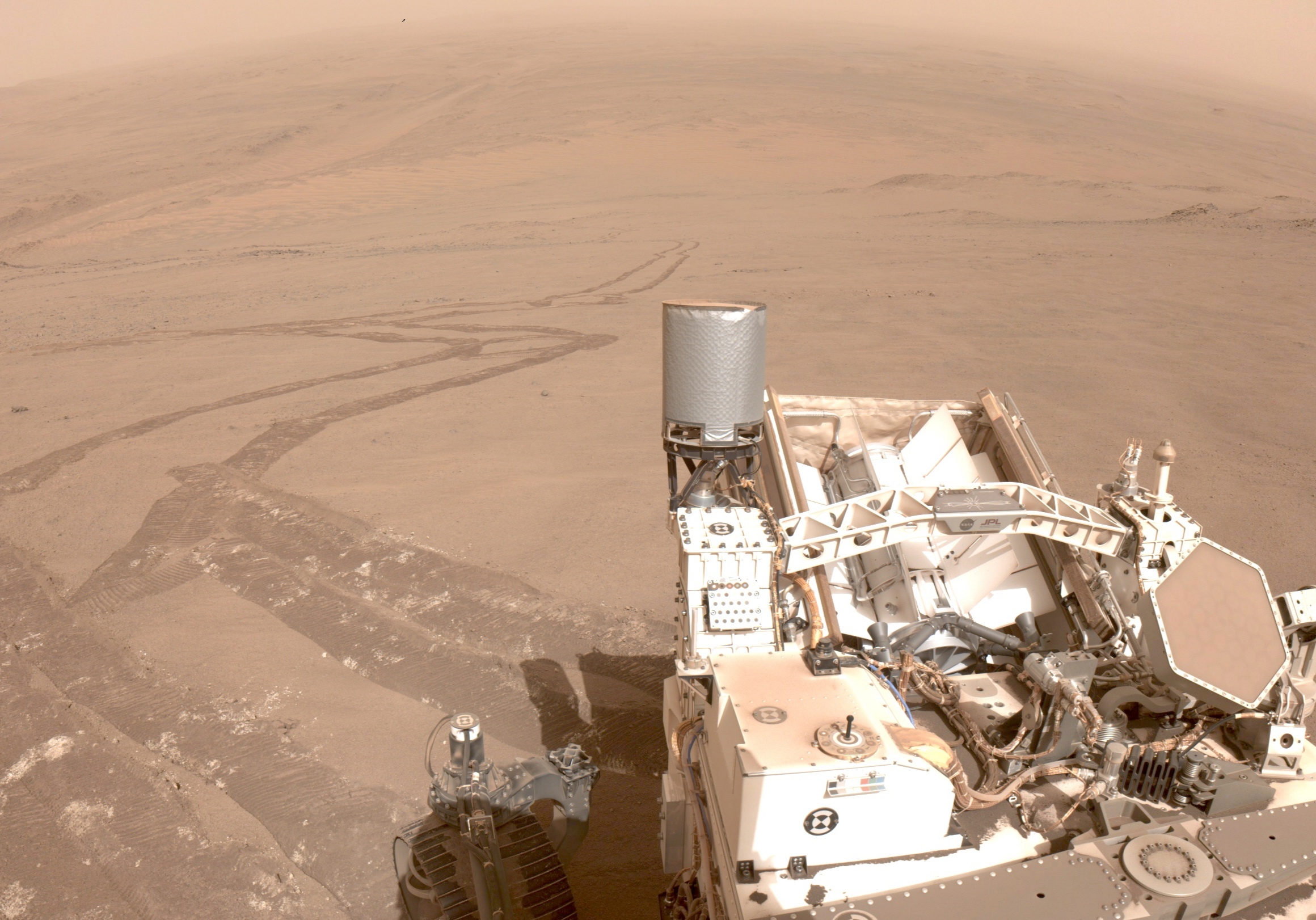

The largest arthropods that ever lived roamed the now-charred forests of the Carboniferous geohistoric period, but based on their fossilized footprints, they didn't avoid open areas either.

It can grow greatly due to two factors: one is the lack of natural enemies, the other is the high concentration of oxygen in the atmosphere, as the poor efficiency of tracheal breathing limits the body size. (In the case of beetles and their companions, in today's conditions, a size similar to a house cat is the upper theoretical limit.)

Based on examination of the stomach contents of arthropod remains, it would have been primarily herbivorous, and secondarily herbivorous, and indeed, to maintain its gigantic body, it would have had to consume a large amount of mixed rotting biomass.

Where is my head?

Centipedes and millipedes belong to the phylum Myriapoda, and their ancestors were the first land animals to breathe. With the exception of predatory centipedes, they live mostly on decaying plants, so they can mostly be found under moist and decaying plant remains, but there are also species that specialize in drier habitats.

Since their lifestyle is not trivial, and their organization is controversial, knowing which mouthparts they chew is crucial to identifying them. Arthropleurans are special in this regard, because although we've known about them since the 1800s, we haven't found a head of pleuropteran arthropods — until now. Of the flat and stained fossils, if largely preserved, fine chitin components are lost.

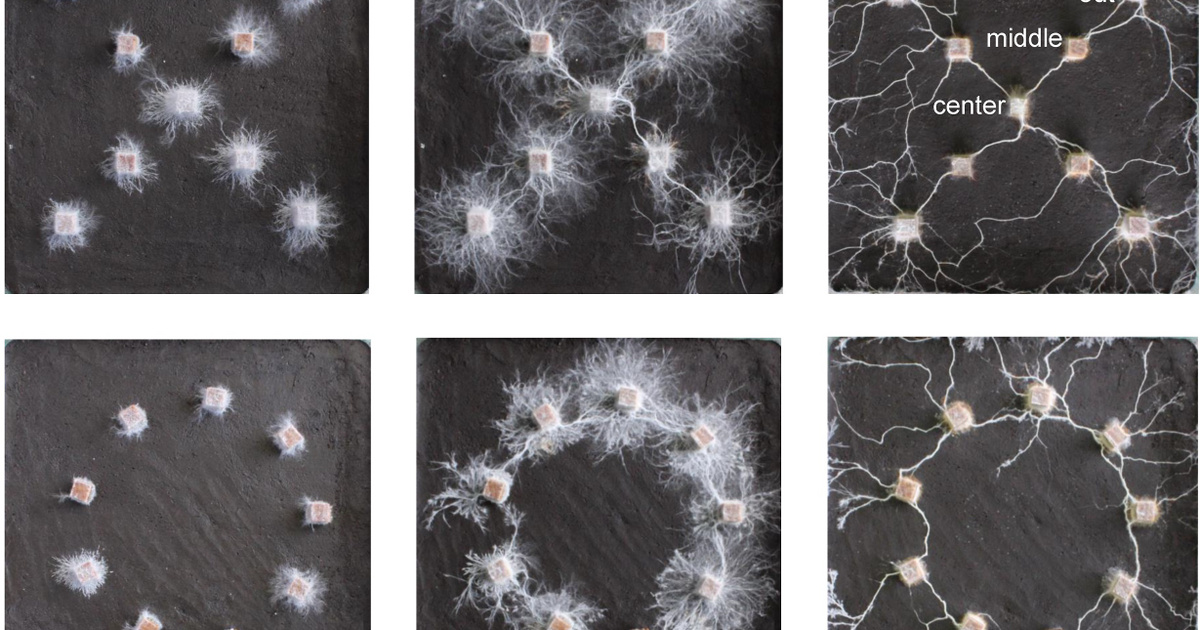

Here comes the role of the student specimens that were found at the Montceau-Les-Mines site in eastern France, including two that were found with intact heads. French researchers took non-destructive computer tomography images of the remains, creating a 3D model based on X-ray CT images. Models made in this way have been compared to the heads of modern millipedes.

The lineage of centipedes and millipedes diverged 100 million years before the appearance of arthropods. For nearly two centuries, it has remained a mystery to which group the giants belonged. Based on their bodies, they resemble centipedes, but the newly found head came as a surprise. The head is a curious mixture of group characteristics, and the long, seven-segmented tentacles are characteristic of millipedes, while the structure of the tentacles is characteristic of centipedes. At the same time, the eyes of Arthropleura protrude from the head on the stalks, which

It does not occur in any group,

Most common in aquatic arthropods such as crayfish.

With these details, it seems that Arthropleura has become a bigger mystery than before. But its chimera-like nature is actually an important piece of evidence upon which the question of the evolution of this species can be answered

Paleontologist James Lumsdale explained.

According to the author of the paper describing the arthropod head, Mikael Léritier of the University of Lyon, the most unusual are the eyes on the leg, which they have not yet been able to locate. According to Lamsdale, an independent professional, this is probably typical of young specimens, and animals roaming the ground may no longer have eyes protruding from the head in their mature form.

(IFL Science, Live sciences, sciences)

![]()