Neurobiologist Roska Botund was a guest on Alinda Veiszer this week. Rosca’s name gained more attention recently when she was part of the research team that helped a partially blind French man regain his sight. The researcher — who is the Hungarian director of the Institute of Molecular and Clinical Ophthalmology (IOB) in Basel — previously spoke in detail with Telex about how the breakthrough was achieved with the help of photosensitive proteins produced in algae, and was the culmination of a 20-year career. from work.

During the conversation, a lot was said about vision and the biology of vision. For example, Ruska talks about how a research method was developed, with which genes are artificially returned to the eye cells necessary for acute vision, namely the cones, with which the retinas of the deceased person’s eyes began to respond to light. . The scientist says that although he predicted twenty years ago that this would be the solution, they were not technically able to implement it. The technology was needed so that the virus-mediated genetic material could reach the spikes, not the so-called ganglion cells. “I’ve been working on this for twelve years, just in address,” he says. Ruska says she didn’t make a statement about her research until she had seen patients in France who she saw what they could do.

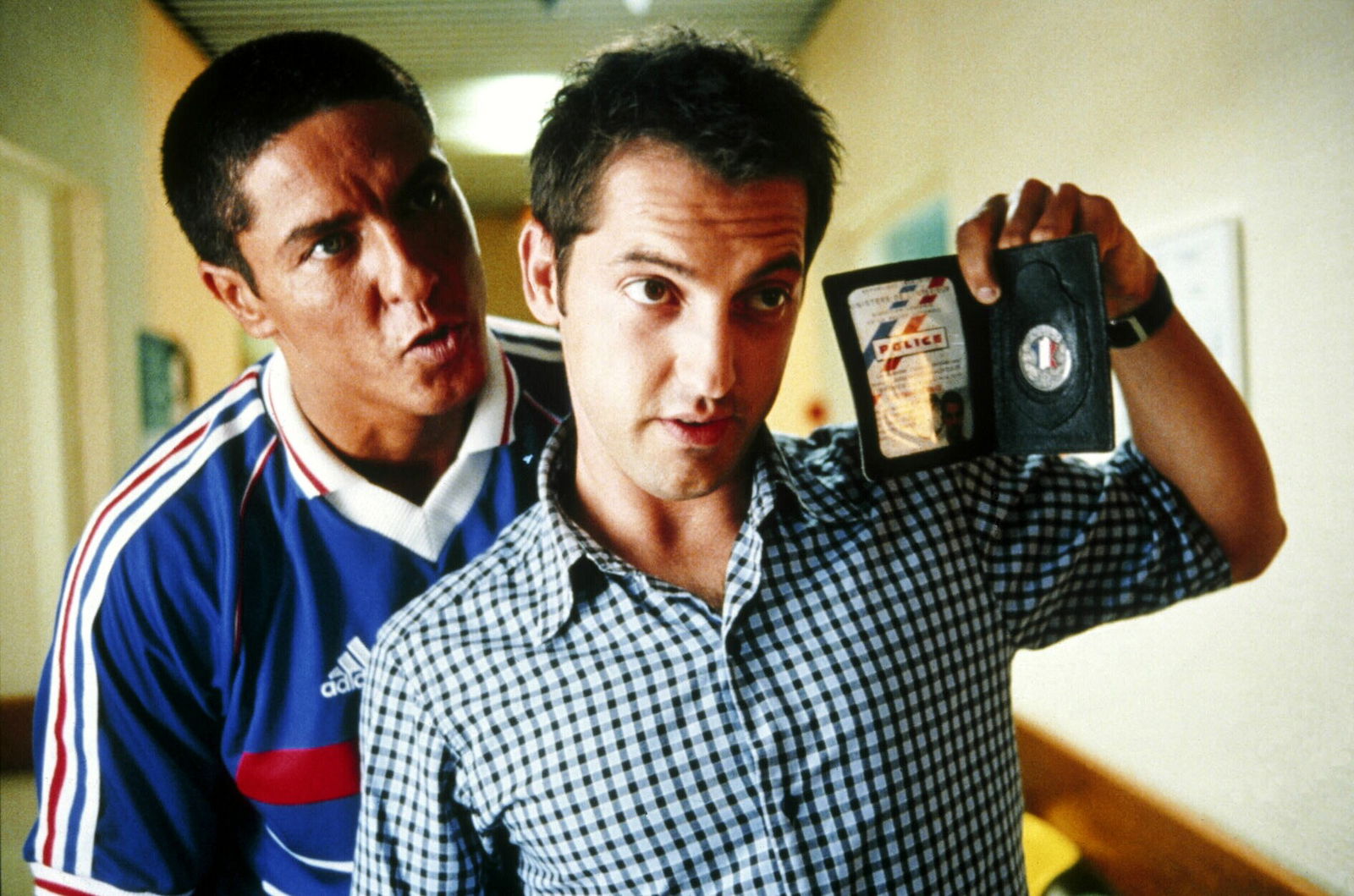

Photo: The Alinda Viser Show

It was developed so that the screws have a “mailing address,” Roska explains, and once you have them, anything can be shipped there. In his case, the thing was a gene that makes the nails start producing a specific protein, a protein that conducts electricity. But it’s also possible to create a gene that doesn’t work there, or to copy DNA there.

There are many more rod cells in the eye than cones, so the question arises of why they are not the key to restoring vision. According to Ruska, this must go back to evolution. Chopsticks are needed in low-light conditions, but modern people don’t need them, because we invented the light bulb. You can tell from the fact that our vision depends on rods that we cannot see colors in the dark. They talk in more detail about the differences and significance of nails and sticks, as well as the development of eye diseases, the research process, and the fact that there was only one person who didn’t see them as completely stupid when they were. Already working on algae in 2008 to improve people’s vision.

According to Ruska, by 2050, myopia will be the cause of most cases of blindness, and two-thirds of people will be nearsighted, with “very serious consequences.” According to the researcher, the chance of developing eye disease is more than six diopters for myopia. The biggest problem is in Asia, where the myopia rate is now 95 percent, compared to 20 percent sixty years ago. At IOB, the focus is now on trying to understand and stop the diseases caused by myopia. They know there is a solution, but they don’t know when it will be found.

According to Ruska, the future will inevitably be that people will face dilemmas in order to buy a car or, for example, to restore their hearing.

Then the scientist says that he persevered a lot in his research because he was “born not to listen much to others.” According to Ruska, science makes mistakes every day, and only those who care not about what other scientists say, but what the data says, can move forward. And for that, it’s worth being stubborn in some way, and it doesn’t hurt if someone has “paranoid enthusiasm” too.

Photo: The Alinda Viser Show

Ruska also talks about why the development of the so-called bionic eye and its connection to the optic nerves will be a problem in the future. The scientist’s father, Tamas Ruska, dealt a lot with the problem of the bionic eye, and his son was very close to him, talked a lot about it with him and even taught him how to think. His day always begins with abstract mathematics: he reads articles and thinks about them, and this helps him to become familiar with the regularity of human thinking. Through these, he can also determine what is important in the science and in the research about it.

Roska Botond was a private student, at the age of thirteen she was going to attend the Piarists, but was taken out of there so that she could attend the Academy of Music. He was tutored by his father, who put a lot of emphasis on probability and differential equations.

“The world is much better described by possibilities than by data,” he says, explaining that data is not important in the world, and he even tells his students to be careful about learning them. To this day, he has no idea what the formula for solving a quadratic equation is.

When asked why he did not become a mathematician, if he was so interested, he replied that the reason was his interest in how the brain works, how we think. She had to stop her career as a cellist due to an injury.

Ruska talks about her language skills, her desire to solve problems, her religiosity (one of her brothers is a priest), how she wants to spend the rest of her time in life, and how much she loves fairy tales. He has two solutions for relaxation from science: music and János Pilinszky.