Based on the rules of private international conflict of law law (which governs the conflict between the laws of individual countries and the resolution of conflicting provisions between them), it must therefore be determined which of the conflicting provisions of Hungarian and foreign law should apply in the case of an employment relationship involving a foreign element.

Staff distribution

With regard to employment abroad, it is useful to apply a certain division of personnel in terms of employment in the European Union. In the European Union, according to the generally accepted understanding, there are those workers who work in another Member State exercising their right to free movement contained in Article 45 of the EUMS (Free Workers), while the largest and most important group is the group of designated workers who are sent to another Member State for a period determined by the company within the framework of the free provision of services (Designated Workers).

General rules for foreign employment

If a Hungarian employer wishes to employ his employees in a foreign country, i.e. outside Hungary, in the labor relationship between the two parties, the so-called foreign element arises. In order to establish the governing law in the employment relationship, it is appropriate first and foremost to determine the personal status law of the parties. By definition, the personal rights of a Hungarian foundation are determined by registration in Hungary. In the labor relationship existing between the Hungarian parties, the provisions of the Labor Code relating to the territorial scope must first be examined, if the place of work originates as a foreign element in the legal relationship.

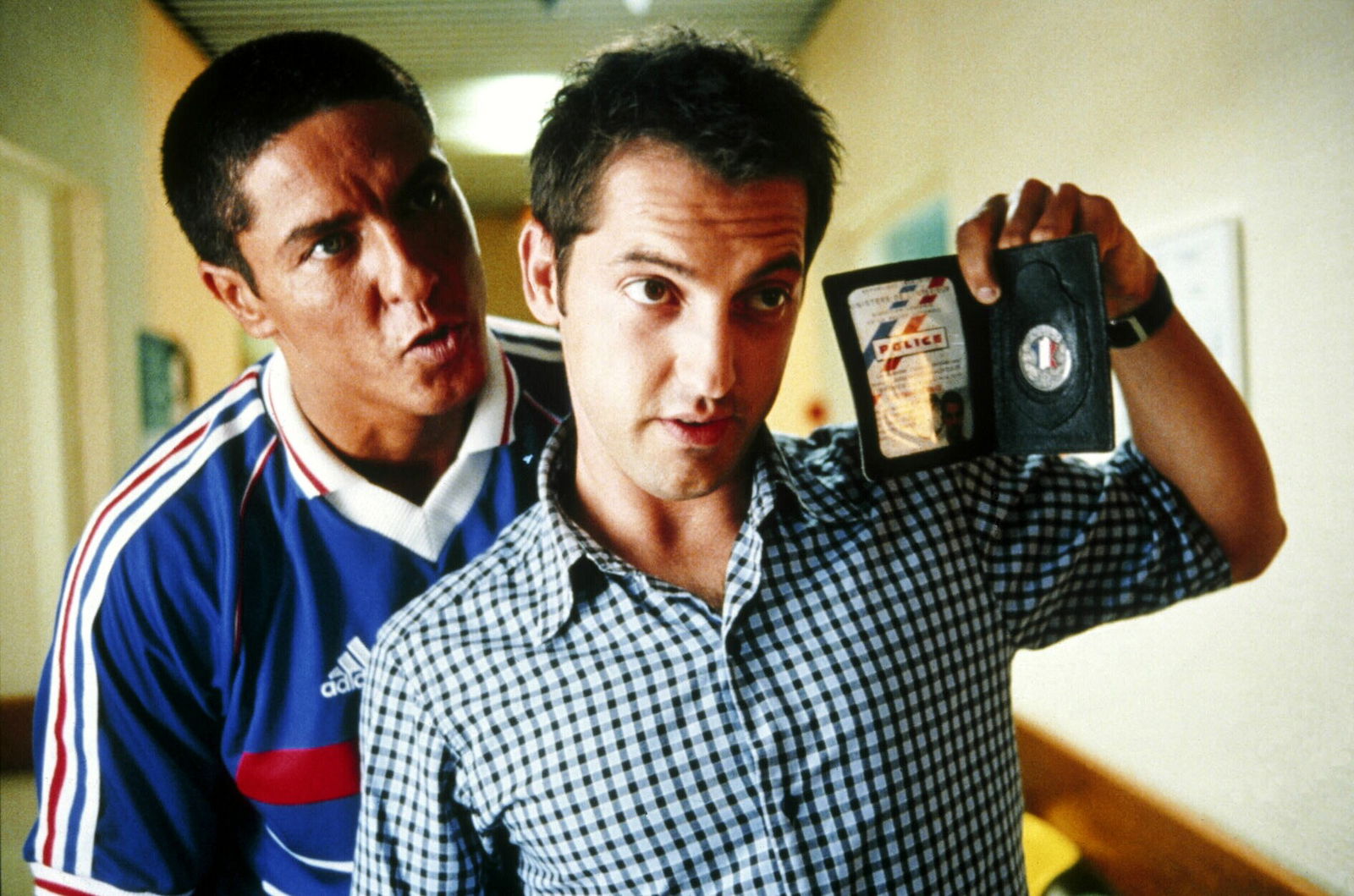

advertisement

According to the Labor Code, its rules must be applied – in the absence of a different provision – if the employee ordinarily performs the work in Hungary (territorial scope). At the same time, it also stipulates that the law must be applied with regard to the rules of private international law.

Based on the rules of private international conflict of law law (which governs the conflict between the laws of individual countries and the resolution of conflicting provisions between them), it must therefore be determined which of the conflicting provisions of Hungarian and foreign law should apply in the case of an employment relationship involving a foreign element.

The European Union has also included its own conflict of laws rules in its legal consolidation processes. In labor relations, the first edict of Rome, which contains special conflict-of-laws rules for contract laws, is the governing body.

The basic principle of Rome I is the parties’ free choice of law, that is, the subjects of the business relationship can freely decide which state law to apply to their legal relationship – if it has a foreign element. While the Hungarian employer is hiring outside Hungary, the employment contract is practically concluded in Hungary according to the rules of the Hungarian Labor Code, which must be written down. In doing so, the persons subject to the legal relationship can – in a clear way – make clear provisions regarding the law relating to the employment relationship. In addition to such an explicit choice of law, the first edict of Rome also assesses the case of an implied choice of law, when it must be ascertained with a sufficient degree of certainty from the provisions of the contract or the circumstances of the case.

Based on practical experience, it is not about the choice of law expressed in many contracts, but the requirement of the competent court (jurisdiction) can often be found. The preamble to the Rome I Regulation states that in determining whether the parties’ choice of law can be determined with sufficient certainty, one factor to consider is the parties’ agreement to grant exclusive jurisdiction to one or more courts in a member state to resolve disputes arising under the contract. Based on consistent legal practice, if other circumstances in the contract do not indicate a different will of the parties, then the law of the state under the exclusive jurisdiction stipulated will be the law according to the implied choice of law.

The question may also arise that if the parties do not specify a specific law in the contract, but a specific rule or set of rules, then it can be considered as a choice of law in the sense that the law of the country to which the specified set of rules belongs will be applied to the entire contract. A good practical example of this is that Hungarian employment contracts, for example, often refer to labor law provisions relating to termination, however, based on consistent jurisprudence, this does not automatically mean the choice of law applicable to Hungarian law. At the same time, the preamble to the Decree of Rome I also notes that the decree does not prevent the parties from incorporating a reference to non-governmental legal documents into their contract, i.e., for example, a reference to the Hungarian termination rules is a partial choice of law and cannot be considered the sole basis for an implied choice of law.

Thus, the choice of law – if there is a foreign element in the employment relationship, i.e. a foreign place of business – eliminates the labor law rule which defines the law of the usual place of work as the applicable law. This principle is confirmed by EUJ C-152/20. (DG and EH v. SC Gruber Logistics SRL), and C-218/20. (Sindicatul Lucrătorilor din Transporturi v. SC Samidani Trans SRL) In consolidated cases, in which the CJEU indicates that the law chosen by the parties to the individual employment contract shall be deemed to be the governing law, and in the absence of a choice of law, the applicability of the governing law (the law of the country of the different workplace, the law of the country of the chosen place of employment shall be) than the law governing the absence of a choice of law, with the exception of the provisions of the governing law in the absence of a choice of law, in respect of which the Rome I regulation does not allow deviation by agreement (See points 2.6 and 2.7).

The applicable law if the law is not chosen

If the parties do not specifically choose the governing law for their business relationship, or because of all the circumstances of the case, an implied choice of law cannot be determined either, the governing law must be drawn up according to the rules of private international law along with the so-called principles of substantive association.

According to the above, the labor law refers to the usual place of work when it defines its territorial scope. The first Rome decree casts a slight shadow over the concept of the usual place of work when it states that not only the place where the employee performs his work in accordance with the employment contract can be considered as a place of work. This wording of the Rome I Regulation is the result of the inclusion of CJEU jurisprudence as a source of law, as is customary in EU law. In fact, the CJEU has made it clear even with regard to the September 27, 1968 Convention on Jurisdiction and Enforcement of Decisions in Civil and Commercial Matters, that if an employee performs his business in several Contracting States, the place of performance of the contractual obligation, according to this clause, is the place from which or from which the employee principally fulfills his obligations to the employer (Case C-125/92). Where the employee’s actual work center is located.In determining this, it is necessary to consider the contractual situation in which the employee spends most of his working time, where his office is located, from where he carries out his activities for the benefit of the employer, and where he returns after traveling abroad for business purposes (Case C-383/95 Rutten v. Cross Medical).

In the case of working in several states, it is therefore necessary to establish a habitual workplace to which the employee’s work can be associated on the basis of the principles of objective communication. Of course, this must be the result of proper consideration, during which all circumstances of the case must be taken into account.

According to the Rome I Regulation, the country of normal employment does not change if the employee is temporarily working in another country. The preamble also helps to clarify the concept of temporary work, when it states that with regard to individual employment contracts, work in another country is considered temporary if, after completing duties abroad, the employee must return to work in his country of origin. The fact that an employee enters into a new employment contract with his original employer or with an employer who belongs to the same work group as the original employer cannot disqualify the employee from being considered to be temporarily working in another country. This usually means cases that occur in practice, when an employee, potentially leaving his domestic employment relationship as it is in the foreign parent or sister company (but actually within a trade group), concludes a new employment contract for the duration of the temporary employment, practically creating a new legal relationship, with the fact that in the event of termination of the new legal relationship, upon his return, the existing Hungarian legal relationship is “fulfilled”.