The online version of the Guardian newspaper reported, Tuesday, that many endangered species suffer from inbreeding, which increases the risk of birth defects, but the lack of genetic diversity can make the animals more vulnerable to other threats, including diseases.

Although scientists have already used frozen cells to create clones in conservation projects, the cells have been stored in liquid nitrogen, which is expensive and risky: if liquid nitrogen is not replenished regularly, the cells will thaw and become unusable. MTI wrote that freeze-dried sperm can also be used for cloning, but not all animals can be obtained.

According to Teruhiko Wakayama, work leader at Japan’s University of Yamanashi, developing countries will be able to store valuable genetic material in their own countries using this technology. Vakagama said the technology could be used to create females for endangered species where only males live.

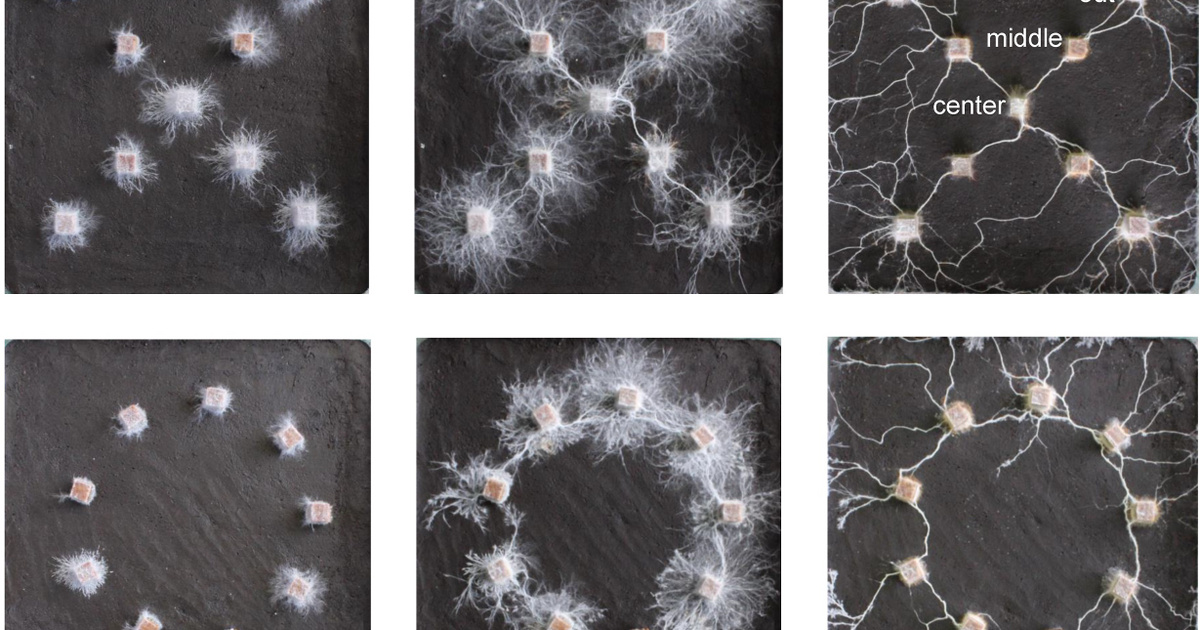

In the latest research, cells in mice tails were frozen and stored for up to eight months before attempting to clone them.

Freeze-drying killed the cells, but the scientists found they could still produce cloned embryos at early stages by transplanting the dead cells into the eggs of mice whose nuclei had been removed.

From these early-stage embryos, called blastula cells, groups of stem cells were created and used for further cloning. Stem cells were implanted into the eggs of mice deprived of their nuclei, and embryos were created that the mice’s mothers could carry.

The first cloned mouse, named Dorami after a popular Japanese manga series, was followed by 74 other mice. Nine females and three males were mated with normal, i.e., non-cloned mice, to check their fertility. All females got pregnant.

Despite the results, the procedure was ineffective, freeze-drying damaged the DNA of skin cells, and the success rate of creating young female and male mice was only 0.2-5.4 percent, the researchers wrote in Nature Communications In the latest issue of the scientific journal