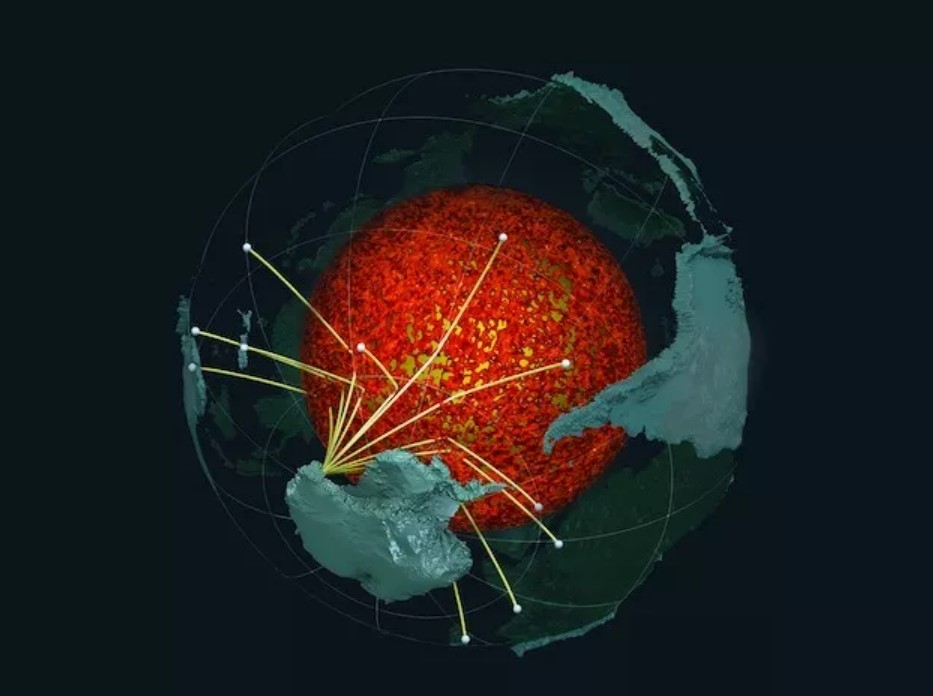

The structure may also affect the planet’s magnetic field.

According to a new discovery, the core of our planet may be completely wrapped in the bottom of an ancient ocean. LiveScience Reports. This thin, dense layer lies approximately 3,200 kilometers below Earth’s surface, between the core and the planet’s middle layer, known as the mantle.

To study Earth’s interior, seismologists measure earthquake waves that travel across the planet and then return to Earth’s surface. By watching how these waves change after they pass through various structures within the Earth, researchers can create a map of what Earth’s interior looks like. Isolated pieces of former oceanic crust near the core have already been identified using this method. In the new research, scientists placed seismographs at 15 stations in Antarctica and collected data over a three-year period. By the way, this is the first study in which high-resolution imaging of the mantle-core boundary has been done using data from the Southern Hemisphere.

The layer under study is very thin compared to the core, which is 724 km in diameter, and also compared to the mantle, which is approximately 2,900 km thick. As one researcher said regarding fish:

The thickness varies by location, with some islands being about 5 kilometers thick while others are 50 kilometers thick.

This ancient ocean layer likely formed when Earth’s tectonic plates shifted, causing parts of the ocean to enter the planet’s interior at subduction zones, where two plates collide and one collapses under the other. Over time, accreted oceanic material builds up at the core-mantle boundary and is pushed up by slowly flowing rocks into the mantle.

Although it is a relatively thin layer, according to the researchers, it still has important functions for our planet. The loose islands of the former ocean floor act as “subterranean mountains” and allow heat to escape from the core. All this is also important because the temperature conditions of this part of the Earth strongly affect the magnetic field of the planet.

(Photo: ASU/Edward Garnero and Mingming Li)