Written by Nadia Drake

Photography by Carsten Peter and Chris Gunn

I started the snowmobile’s engine, and it blasted across the field of snow and ice, shining in ethereal shades of blue. I’ve been wandering around the frozen fjord all day, and now I’m back in the largest settlement on Svalbard (Spitzbergen). Norway’s mountain-studded archipelago

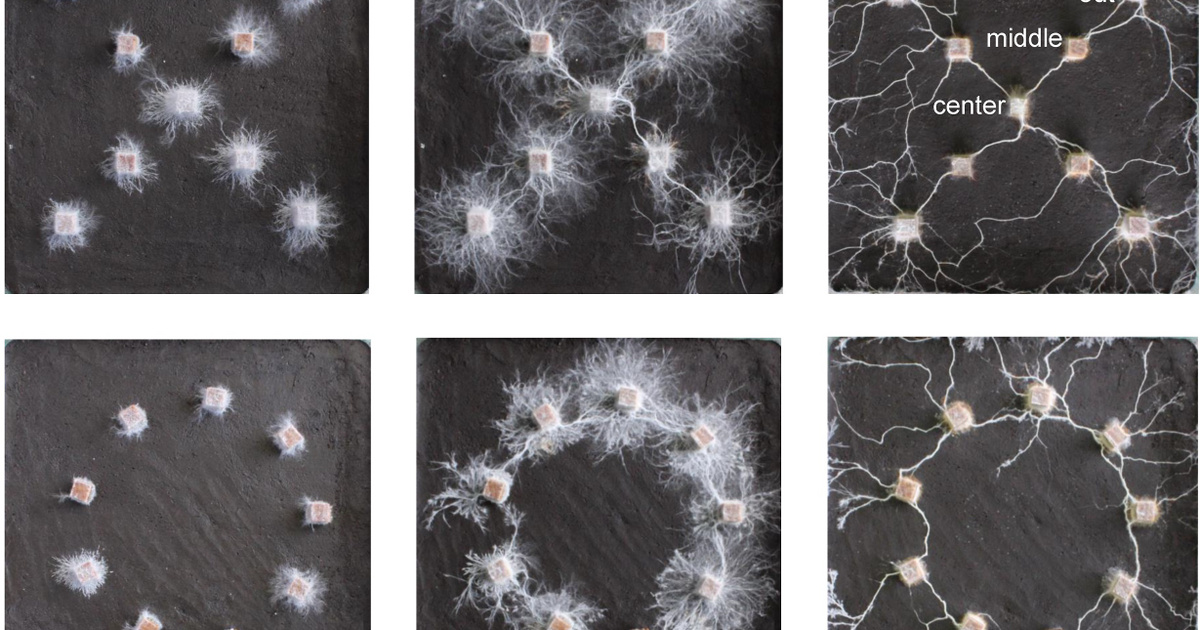

The northern light often dances above, and around it roam the narwhals, belugas, and walruses of the Arctic Ocean. We write in March, a month after the sun finally returned to the sky. With six researchers, we’re looking at mounds of ice that grow out of the ground, pingos, and, more specifically, we’re interested in the microorganisms that can be found in them. Ice lenses that form in permafrost, ranging in size from a small bump to a serious mound, rise above ground level as a result of cycles of freezing and thawing. They act like cryovolcanoes – only in very slow motion. Here researchers wear warm clothes, as they have to visit water and ice sampling sites several times a day in freezing temperatures of -26 degrees Celsius. They also carry a rifle, just in case they need to scare off a wandering polar bear.

Photographer Carsten Peter uses a drone in Norway’s Svalbard (Spitzberg) to photograph the region’s largest glacier lens, Alpengo, to show its dimensions. Microbiologist Dimitri Kalinichenko is interested in the microorganisms found in the pingo ice and the water beneath it; It’s also in the photo, doing business on a nearby rock bench, but it’s hard to see in twilight.

Source: Peter Carsten

Astrobiologist Kevin Hand (right, on one knee) and Dimitri Kalinichenko (far right) sample ice from Pingo near the town of Longyearbyen. Survival strategies that allow microorganisms to survive the low-light and extreme cold conditions here could also work on the solar system’s icy moons.

Source: Peter Carsten

Microorganisms living in Bingo could offer a clue about possible life on other celestial bodies in the solar system, and on icy moons with oceans hidden beneath their icy surfaces. In winter, “they cannot obtain solar energy, and can only rely on chemical energy,” explains project leader Dimitri Kalinichenko, a microbiologist at the University of Tromsø.

Kenny Broad (center) and Nadir Quarta (right) prepare to dive into Lago Verde within the Frasassi cave system in central Italy with the help of caver Valentina Mariani. The dark, toxic waters teem with an astonishingly large variety of microorganisms. It is likely that some of the organisms living here operate one of the oldest types of metabolic processes: they use hydrogen sulfide with a scent that hits the nose. Ecosystems isolated from sunlight can be good examples of important life-creating processes that can occur in the oceans of icy moons.

Source: Peter Carsten

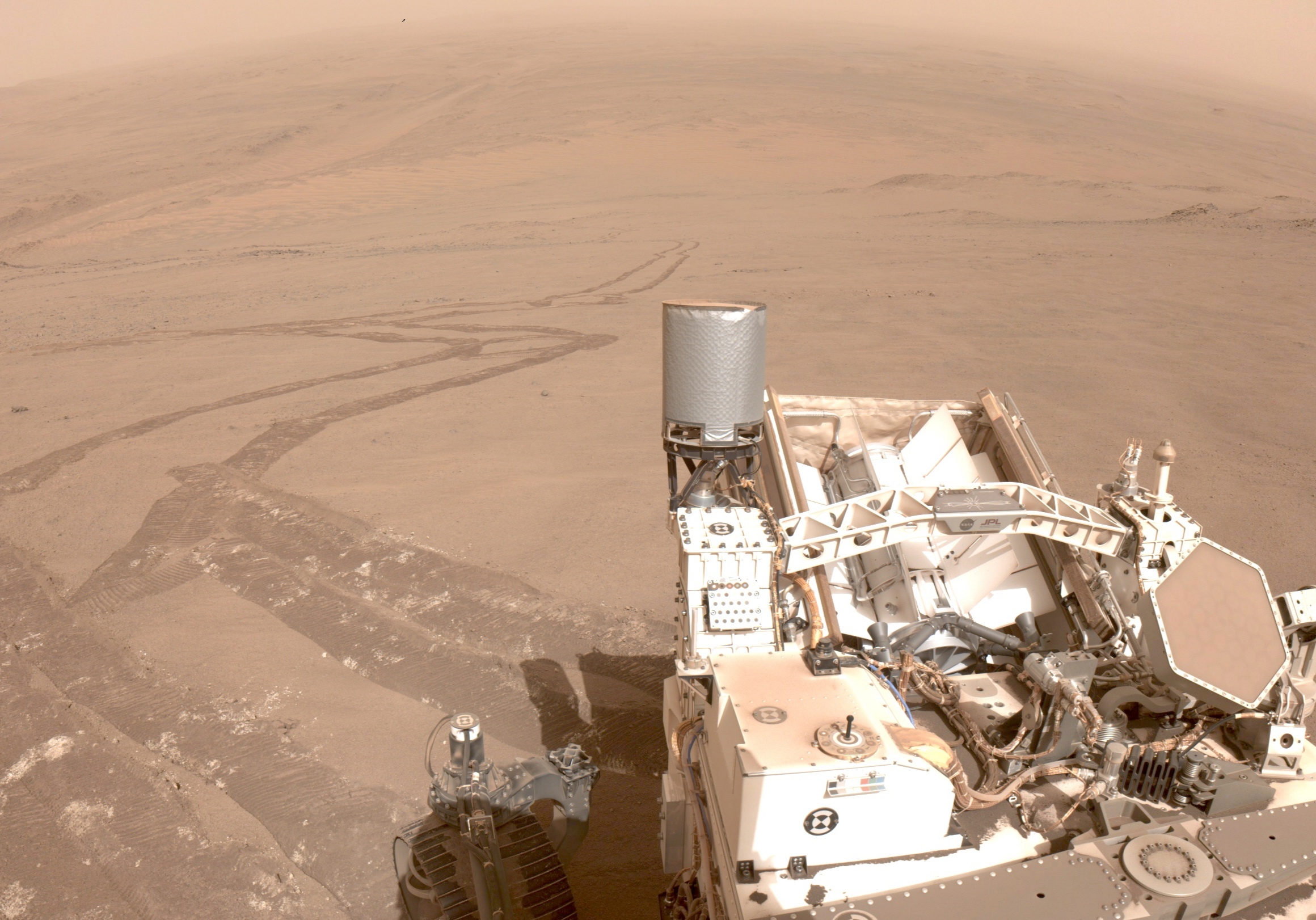

The Aurora hydrothermal vent field, which extends beneath the permanent ice cap of the Arctic Ocean at a depth of 4 km, is likely another landscape similar to the ocean floor of Enceladus and Europa orbiting Jupiter. In 2021, with the remote-controlled submersible Aurora, it has become possible to sample the liquid mixture flowing from one of the passages, Ganymedes, so it is hoped that many new things will be revealed about the chemical reactions that provide energy to aliens. Deep sea ecosystems in the absence of sunlight.

Source: Still from REV OCEAN/HACON video recording

We learned relatively late that it is possible to live on Earth without sunlight.

“For a long time, we thought that life on our planet was largely concentrated on the surface, and that life depended entirely on photosynthesis,” notes Barbara Sherwood Lollar, a geologist who studies underground microbes at the University of Toronto. Then, in the late 1970s, the submersible Alvin found a hydrothermal vent teeming with living organisms in the dark, two and a half kilometers below the surface of the Pacific Ocean, in the vicinity of the Galapagos Islands. However, it was the previous voyage that assumptions about the limits of life had become invalid. “Knowing that even here on Earth we can discover new and completely unknown life forms and habitats teaches us humility.”

Sherwood Lollar confirms. Previously, experts also assumed that the habitability of any celestial body depends on its distance from the Sun. But this picture is not complete. There are three distant moons in the solar system, warmed by the gravity of their giant planet, and in their oceans we hope to find traces of extraterrestrial life: one is Jupiter’s moon, Europa, which has more water under its ice cap than in its oceans. And in the Earth’s oceans combined; The other is one of Saturn’s moons, the small Enceladus, from under whose ice cap the waters of the World Ocean erupt at the cracks of the Antarctic; The third is also Saturn’s moon, Titan, whose surface is covered in lakes filled with liquid hydrocarbons, and inside which an ocean hides. Thus, all three moons contain water, energy and chemical elements necessary for life that we know – or even unknown – for life…

You can read the full article in the October 2023 issue of the magazine.