The development of science and technology is, if not halting, but truly breakthrough inventions and discoveries are becoming increasingly rare, according to a study conducted last year that established all this. Now a new study has tried to refute the previous statement, but the question is how successful it is.

Electric cars, high-speed phones, artificial intelligence, and even the promise of fusion energy production – all of this seemed like science fiction not so long ago, but today it is either part of everyday life, or is greatly developed. How serious. On the other hand, lunar missions are declining, there are huge gaps in our understanding of the universe, the smartphone itself will soon be 20 years old, and although there have been attempts to replace it, especially recently, nothing has been found. Among them were those who succeeded in deposing:

The revolutionary AI pin was a huge flop according to early reviews

It overheats, gives unreliable responses, and is slow and even expensive.

So where is the truth:

Is science and technology accelerating or stagnating?

Last year, we wrote about a study that tried to measure all of this and came to a very bleak conclusion — said the study's lead author, Michael Park, While previous research has shown a decline in individual specializations, the 2023 study is the first to

“It empirically and convincingly documents the decline of this disruptive influence in all major areas of science and technology.”

Park called these discoveries “discoveries that break with existing ideas and take the entire field of science to new dimensions, discoveries that have a disruptive effect on science and technology.” The current study classified 45 million studies between 1945 and 2010 and 3.9 million US patents between 1976 and 2010 accordingly. From the beginning of these periods, research materials and patents were more likely to draw on prior existing knowledge. The ranking was based on how given articles were cited in other studies five years after publication, on the assumption that the more groundbreaking research, the less previous articles on the topic are cited. However, breakthrough discoveries are emerging more and more slowly, and their greatest decline has occurred in the natural sciences, such as physics and chemistry.

The story continued this year with a study trying to refute the results of the above research, which Sabine Hosenfelder reported in the video above. Hosenfelder introduces the topic by saying that the current situation is somewhat paradoxical: research productivity is decreasing even though there is more and more of it in the scientific world and publications are being produced at an unprecedented rate. Thus, while the number of scientists worldwide has increased in proportion to the population, especially in developed countries such as Germany, the quality and impact of scientific research appears to be declining.

the Current new publication However, he seems to question these findings – he is “Is there a long-term decline in disruptive patents? Correcting for measurement bias.” According to the article, the proportion of “disruptive” innovations, measured in 2023 on the basis of patents, has not decreased significantly in recent decades. The authors of the paper argue that previous results were biased by citation gaps, particularly excluding citations to patents before 1976.

The authors of the article specifically claim that previous research produced biased results because it excluded references to patents before 1976. As a result, older patents appeared to have a more revolutionary (disruptive) impact, as fewer references to them were counted, so Giving them artificially higher values. This bias resulted in post-1976 patents appearing less troublesome because references to earlier patents were missing from the analysis. The authors corrected this error and found that the decline in the rate of disruptive innovations was not as large as previously thought. Although there has already been some decline, the data does not support a significant decline in the long term.

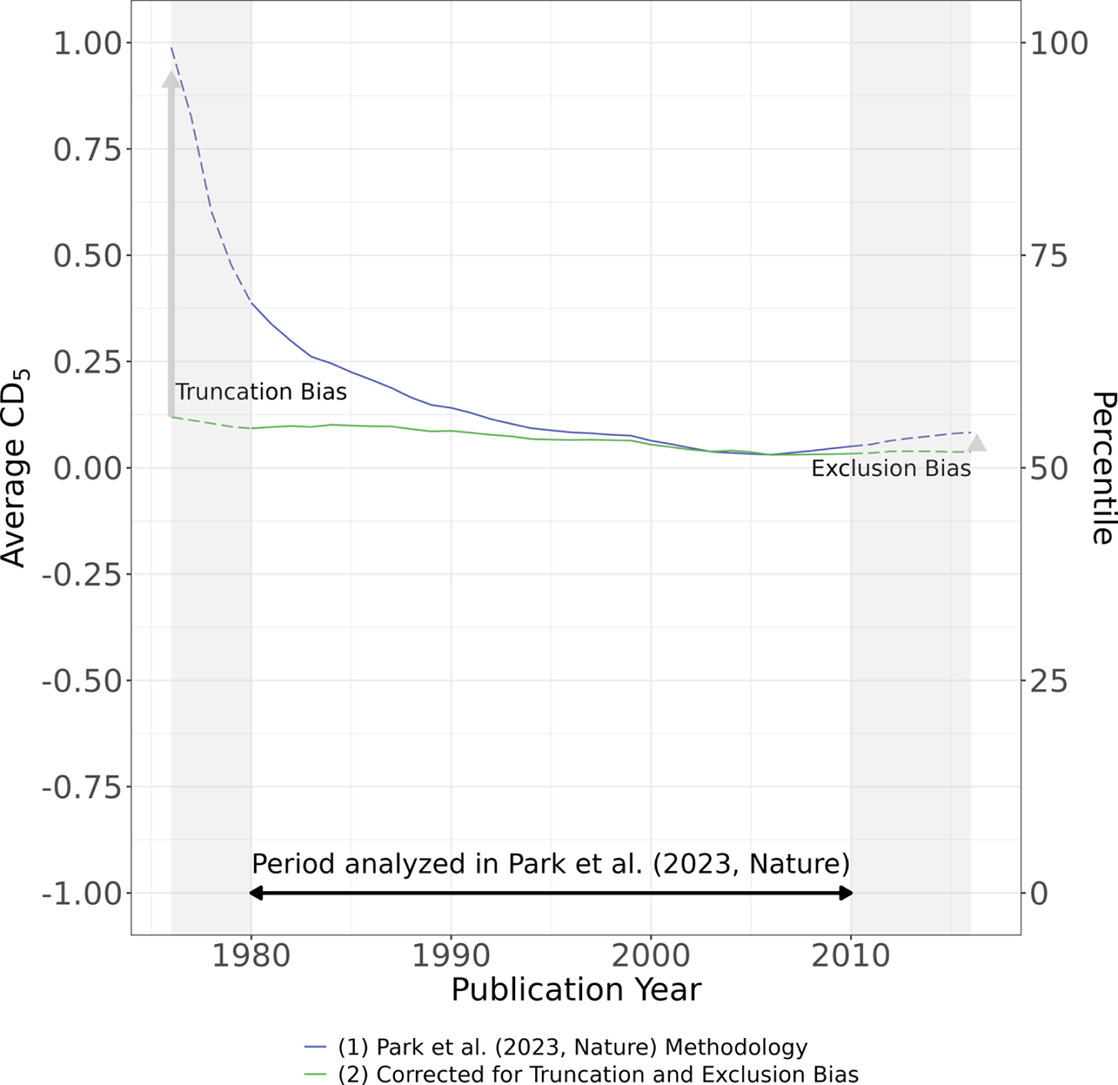

However, according to Hosenfelder, the revised results also indicate a decline, even if the difference is not as sharp as in the 2023 study. To see who is right, let's examine the two results on the chart:

The graph shows two curves:

- Park et al. (2023) Methodology (blue line): This methodology therefore did not take into account patent references before 1976 (truncation bias), resulting in truncation values that rose in the early 1980s and then showed a sharp decline.

- Corrected methodology (green line): This curve corrects for citation gaps, taking into account patents before 1976 (exclusion bias). The result shows a more balanced trend, based on the fact that the decrease in turbulence is not as large as previously thought.

Based on the above, it is a far cry from the dramatic range scheduled for 2023, but revolutionary inventions are slowly but surely diminishing, although the number of scientists on the planet is increasing. The question is, what are we certain from all of this: that the decline in disruptive inventions is not that dramatic, or that such a decline actually exists, despite apparently favorable conditions in the world of science and technology (many scientists, many studies).

Incidentally, the 2023 study also addressed possible reasons for this decline – one of which is the low-hanging fruit theory, according to which fruit is first collected very easily and very quickly from the more easily accessible lower branches of trees. The larger, but relatively easy, finds are now starting to run out slowly. However, according to Park, this belies the fact that this slowdown affects all major fields of science with roughly the same speed and timing, whereas according to the low-hanging fruit theory, it would occur on a larger scale, since the distribution of major disciplines but easy discoveries also varies from field to field. last.

For this very reason, researchers suspect something else, an effect they call research burden. Consequently, researchers today have so much to learn to become experts in a given field that there is little time left to do truly pioneering work. For this reason, scientists and inventors focus on a narrow slice of knowledge that already exists, and their work tends to reinforce this knowledge that already exists and does not achieve a true breakthrough. Added to this is the need for publication in academic life today, where researchers receive degrees based on published and cited studies.

(Image: Pixabay/Yarmoluk)