Credit: Pixabay/CC0 Public Domain

Researchers at the Francis Crick Institute, working with Imperial College London, King’s College London, and the University of Cambridge, have shown that the flow of water and ions to immune cells allows them to migrate to where the body needs them.

Our bodies respond to illness by sending chemical signals called chemokines, which tell immune cells called T cells where to go to fight the infection. This process has actually been linked to a protein called WNK1, which activates channels on the cell surface, allowing ions (salts such as sodium or potassium) to move into the cells. Until now, it has not been clear why an influx of ions is needed for T cells to move.

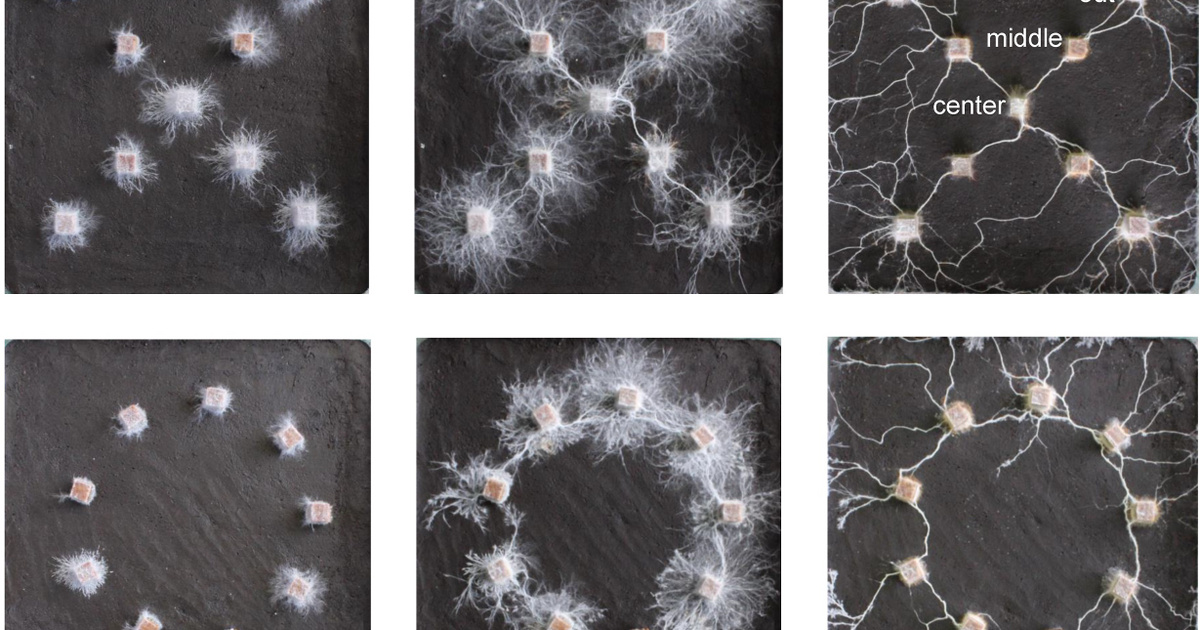

Through a study published in Nature CommunicationsThe researchers imaged murine T cells and observed that following a chemokine signal, WNK1 is activated at the front of the cells, called the “leading edge.”

The team showed that WNK1 activation opens channels on the leading edge, leading to an influx of water and ions. They suggest that this influx of water causes the cells to swell on the front side, creating space for the “actin cytoskeleton” to grow – the scaffolding inside the cell that holds up its structure. This pushes the entire cell forward and the process is repeated again.

The researchers used gene editing to stop the mice from producing WNK1, or an inhibitor to block WNK1 activity, and observed that the T cells in these mice slowed down or stopped moving altogether.

More importantly, they found that they could compensate for the loss of WNK1 and make the cells accelerate by dropping them into an aqueous solution, which made the cells absorb water and swell. This indicates that water absorption, controlled by the WNK1 protein, is key to cell migration.

The researchers believe that the mechanism they discovered could be involved in many different cell types outside of immune cells.

“With this research, we have unraveled one of the mysteries of T-cell movement, showing that WKN1 causes the influx of water and ions into T cells,” said Victor Typolowicz, group leader of the Immune Cell Biology and Down Syndrome Laboratory at the Crick. T cells, giving them space to grow their scaffolds and move forward. “Even though we looked at T cells, it is likely that this process occurs in many of our own cells and even in diseases such as cancer, which is important because when cancer cells spread, they are difficult to treat.”

“This process has been speculated for decades, but advances in technology have finally allowed us to show how WNK1 helps T cells migrate around the body,” said Leon de Boer, a former postdoctoral researcher at Crick and now at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden. “Almost like a jet engine propelling the cell forward.”

“I’m excited that researchers are starting to study WNK1 inhibitors to treat diseases like cancer. In my new project, I’m investigating how membrane properties help cancer cells move around the body.”

more information:

Leonard L. De Boer et al., T cell migration requires ion and water influx to regulate actin polymerization, Nature Communications (2023). doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-43423-8

the quoteLanguage programming

This document is subject to copyright. Notwithstanding any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.