Researchers suggest that the taste of fermented morsels may have led to a sudden jump in the growth rate of our ancestors’ brains.

In fact, the shift from a raw diet to one that includes nutrients partially broken down by microbes may have been a crucial event in the evolution of our brain. According to a perspective study It was conducted by developmental neuroscientist Katherine Bryant of the University of Aix-Marseille in France and two American colleagues.

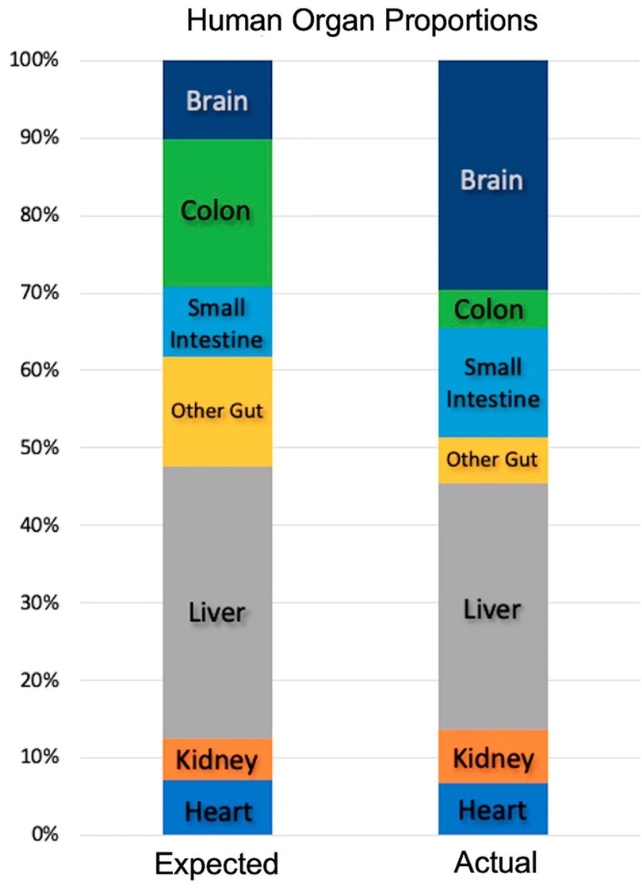

Human brains have tripled in size over the last two million years of evolution, while human colons have shrunk by an estimated 74%, indicating a reduced need to break down plant-derived foods internally.

We do know the timeline and extent of the expansion of the human brain, however Mechanisms that allow energy to be directed This expansion is more complex and somewhat discussed.

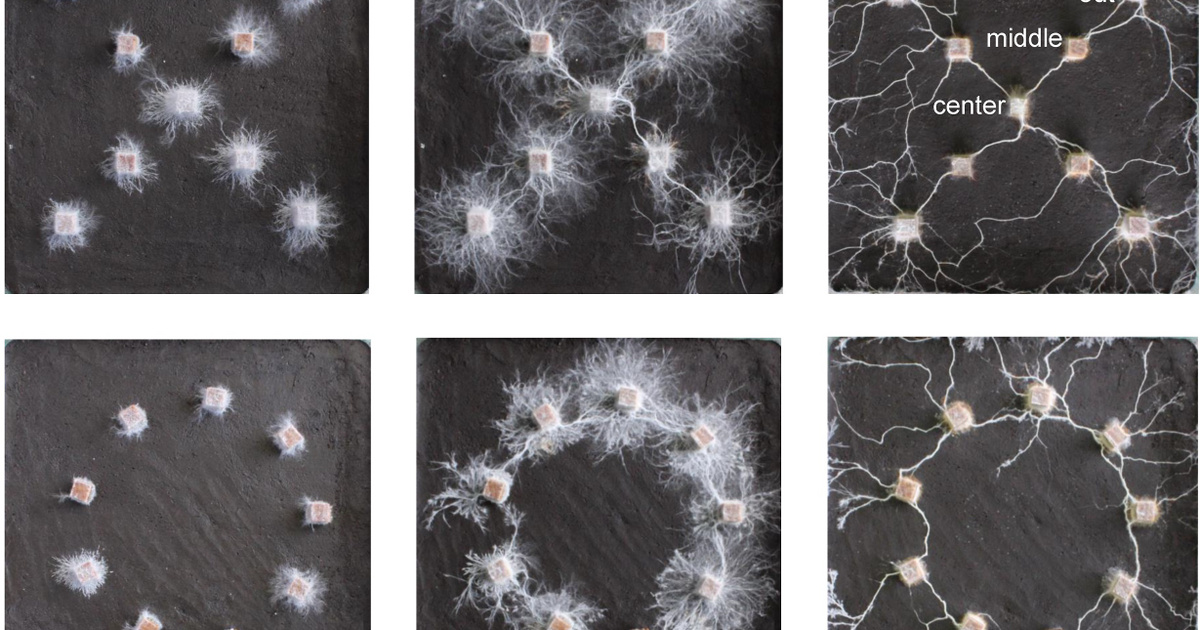

Study authors Planning Their “external fermentation hypothesis” explaining the metabolic conditions for our ancestors for selective brain expansion may have been initiated by transferring intestinal fermentation to an external process, perhaps even experimentally With preserved foods not unlike wine, kimchi, yogurt, sauerkraut, and other pickles we still eat today..

The human gut microbiome acts as an internal fermentation machine, enhancing nutrient absorption during the digestive process. Organic compounds are fermented To alcohol and acids through enzymes, usually produced by bacteria and yeasts that live in parts of the digestive system such as the colon.

Fermentation is an anaerobic process, meaning it does not require oxygen, so it is similar to the process that occurs in our intestines, and can occur in a sealed container. The process produces energy in the form Adenosine triphosphate (ATP), an essential source of chemical energy that supports our metabolism.

The researchers suggest that it is possible that culturally inherited ways of handling or storing food have encouraged the externalization of this function.

Externally fermented foods are easier to digest and contain more available nutrients than their raw counterparts. Since the colon can’t do much if the food is already fermented, its size can diminish over time, potentially leaving energy available for brain development.

The brain sizes of our ancestors AustralopithIt was similar to that of chimpanzees (Pan caves) and bonobos )Pan Paniscos). The human race’s brain expansion accelerated with HomoAppear and continue through A wise man And Neanderthal.

How did our ancestors, with brains the size of chimpanzees, harness the power of external fermentation?

Bryant and her team suggest that humans with lower cognitive abilities and smaller brains may have adapted to fermentation much earlier than alternative explanations proposed for redirecting energy from the gut to the brain, such as hunting animals and fire-based cooking.

Fermentation has many advantages associated with cooked foods, such as more tender texture, increased calorie content, improved nutrient absorption, and defense against harmful microorganisms.

It only needs simple storage spaces like a cavity, cave, or even a hole in the ground, and it’s basically a low-key, stress-free ticket to nutritional goodness. As the researchers point out, “it can be found rather than requiring planning and use of tools.

“Hunting, hunting for large carnivores, and the use of fire carry their own risks;” Bryant and his colleagues He writes“Perhaps the risks of fermentation were more predictable and thus could be more reliably mitigated through individual and cultural learning.”

In addition to increasing the bioavailability of nutrients, exogenous fermentation can also make toxic foods edible, for example by Cyanide removal A common staple food cassava (Manioc Esculenta).

“Thoughtful and mechanical understanding are the two no Requirements for the initial appearance of external fermentation” He writes Researchers. “Our early ancestors may have simply carried food to a common place, left it there, intermittently eating some and adding more.”

Microbes from previous foodstuffs may have inoculated new foodstuffs, resulting in fermentation. As brains grew larger, humans may have developed a better understanding of fermentation.

The team emphasizes the need for experimental research to support or refute their hypothesis, such as microbiological studies, comparative analyses, and genetic and genomic investigations.

“Unpacking the enteric fermentation process into an exogenous cultural practice may have been an important hominin innovation,” the authors say. We conclude“which identified the metabolic conditions necessary for selection for brain expansion to occur.”

The study was published in Communication biology.