In May 2023, just days after the LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA gravitational wave detector collaboration resumed, an instrument at LIGO's Livingston Observatory detected a gravitational signal from the collision of what is believed to be a neutron star with another compact celestial body. The special feature of the event cataloged under the number GW230529 is that the largest celestial body involved in the collision was 2.5 to 4.5 times larger than the Sun. Experts have never observed a compact celestial body of this size before.

We know of two types of compact celestial bodies, neutron stars and black holes. Both types of objects are created as supernova remnants. Black holes are typically more massive and denser than neutron stars, but their gravitational signatures make them nearly impossible to tell apart. Before gravitational wave observations began in 2015, small black holes with a mass similar to that of our Sun, or stellar mass, were primarily detected using X-ray telescopes, while neutron stars were detected using radio telescopes. The observed mass ranges for the two types of celestial bodies are clearly separated from each other; Neutron stars have a mass of approx. It was found that its mass was less than 2 solar masses, while the mass of black holes was approximately greater than 5 solar masses.

Thanks to gravitational wave measurements, experts have already been able to determine with relative accuracy the mass of about 200 newly discovered compact celestial bodies, but since then very few candidates for objects with masses between 2 and 5 solar masses have been found, one of them – one of the participants In the event called GW190814 – it was reported by us four years ago here, on czillászatza.hu. Meanwhile, astrophysicists have been debating ever since whether any candidate can be clearly proven to fall into this empty mass gap.

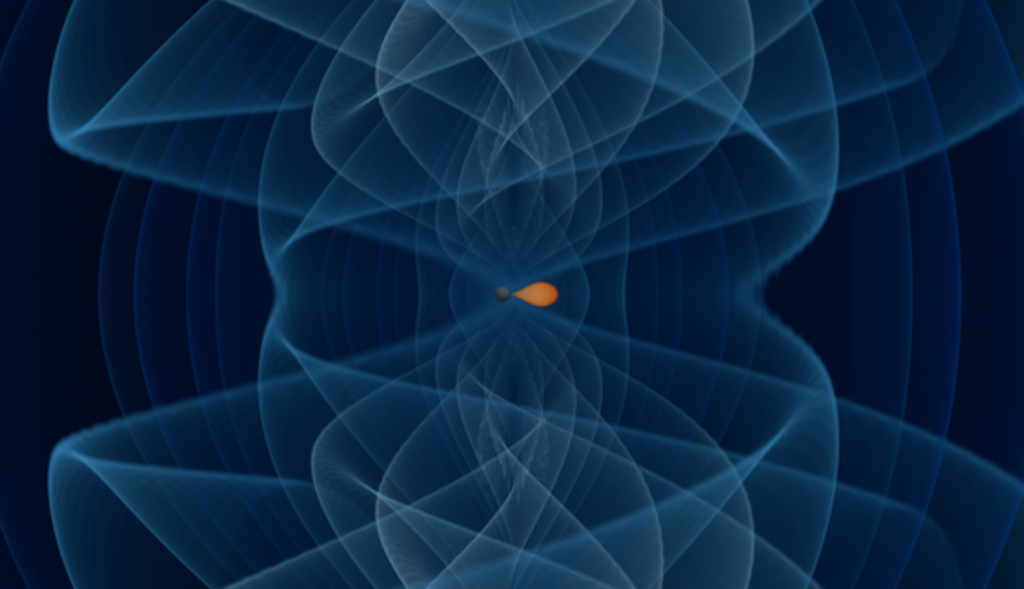

In a newly published gravitational wave event called GW230529, a smaller celestial body with a mass between 1.2 and 2 solar masses merged with a larger compact celestial body of just over twice that mass. Thus, despite the measurement uncertainty, it is clear that the larger object fell into the previously empty mass gap shown above, which may settle the debate about the existence of such celestial bodies.

The gravitational wave event GW230529 arose from the last milliseconds of two compact objects orbiting and spiraling into each other. The collision created a black hole with a larger mass, but a significant fraction of the system's initial total mass was emitted into outer space as gravitational wave energy – thanks to this, we were able to observe the merger from a distance of about 650 light-years, from here on Earth.

Although the signal detected in gravitational field oscillations does not clearly identify the exact type of celestial body, it is very likely that the smaller object was a neutron star, while the larger object was a black hole. LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA researchers are also quite certain that the mass of the black hole involved in the collision fell into the mass gap, so it is truly special.

Gravitational wave detectors that are truly suitable for cosmic observations are relatively new instruments, having only been operational for less than a decade. The observations are divided into periods of approximately 1 to 1.5 years, with similarly long pauses in between. In such cases, the sensitivity of the detectors is maintained and improved.

GW230529 was discovered by LIGO's Livingstone detector in the early days of the O4 detection period. Unfortunately, due to the early time, other collaboration tools were not yet working, so the specialists were unable to determine the direction in which the signal was arriving. For this reason, despite the alert being raised by optical telescope systems that scan the sky within minutes of detection, the phenomenon's aurora – if there was any at all – was never found.

The continued development of gravitational wave instruments will make it possible to observe more and more similar and even different events, so we can expect more exciting news in this area.

source: LIGO Scientific Collaboration

comment