The largest sponge bleaching to date has been carried out off the coast of New Zealand. According to researchers, tens of millions of sponges may have been affected by the long sea heat wave, according to the online edition of the British daily The Guardian, according to MTI.

Researchers first sounded the alarm in May when they spotted bleached sea sponges off New Zealand’s southern coast. Their investigation found that as many as tens of millions of sponges had turned white. “To our knowledge, this is the largest sponge bleaching reported in a single event, especially in cold water,” he was quoted as saying. James Bell The British newspaper quoted the professor, a marine ecologist at the University of Victoria.

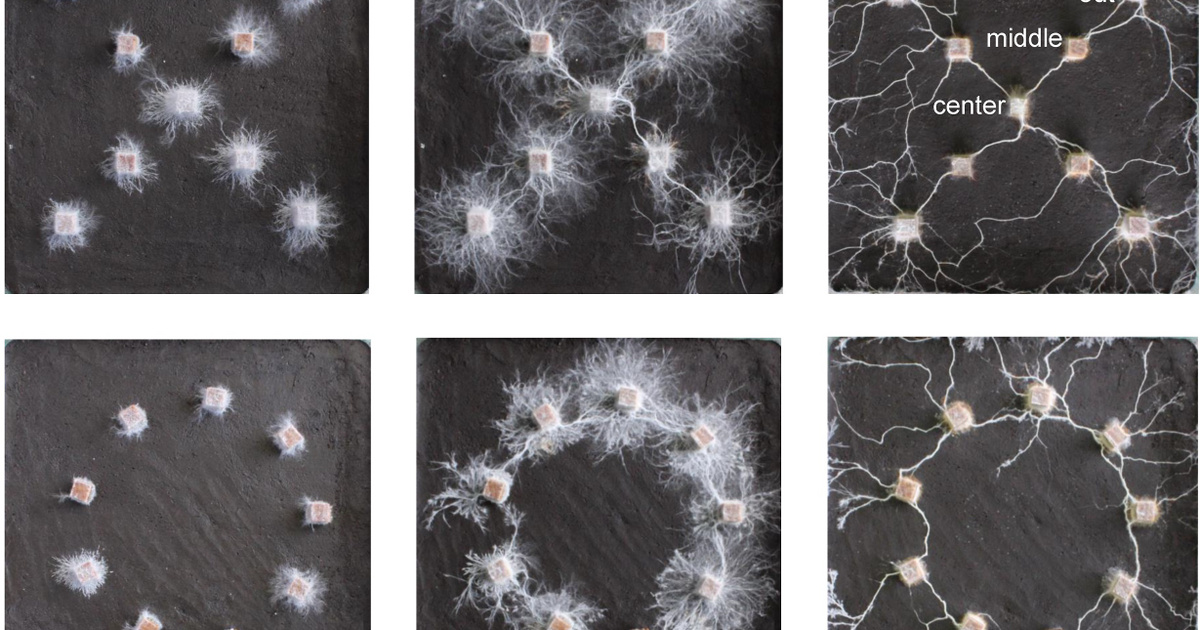

Sea sponges, like corals, depend on symbiotic organisms to photosynthesise, provide food, and sometimes deter predators. Although bleach doesn’t necessarily kill the sponge, it does push these organisms away — lowering the sponge’s chemical defenses and depriving them of food. While some species can recover from severe bleaching, Bell says others cannot.

Robert SmithTwo waves of sea heat around New Zealand have pushed the ocean up to a record temperature, in some areas five degrees warmer than usual, a University of Otago oceanographer said. And the scientist confirms: “At the northern and southern borders of New Zealand, we have experienced the longest and strongest sea heat wave in the past 40 years, since satellite measurements of ocean temperature began in 1981.”

He pointed out that the sea heat wave started in some areas last September and just ended, and lasted 213 days, noting that this is a somewhat unusual phenomenon.

According to Smith, it is difficult to attribute individual heat waves to the man-made climate crisis, but ocean temperatures are rising around the world. “Over the past century, the frequency, duration and intensity of marine heat waves have increased dramatically worldwide,” he said. These heat waves are expected to become more intense and longer in the future. “We now have a glimpse of what our oceans will look like for our children and grandchildren,” Smith warned.