According to geochemical evidence found at the presumed impact site of Chicxulub, Mexico, the object that hit Earth and started the extinction event that wiped out all dinosaurs except birds 66 million years ago was an asteroid that originally formed outside the orbit of the planet Jupiter.

the sciences In its new issue Published The results suggest that the mass extinction was the result of a series of events that occurred at the birth of the solar system. the beginningResearchers have long suspected that the Chicxulub crater may have been formed by an asteroid from the outer Solar System, and the new findings confirm this claim.

The Cretaceous–Paleogene (C/Pg) extinction event was the fifth in a series of mass extinctions that occurred over the past 540 million years or so, a period in which animals became widespread on Earth. This event resulted in the extinction of more than 60% of species, including all non-avian dinosaurs.

Since 1980, evidence has mounted that the extinction was caused by a city-sized object hitting Earth. Such an impact could have sent huge amounts of sulfur, dust and soot into the air, partially blocking out the sun and cooling it. A layer of iridium, rare on Earth but more common in asteroids, was deposited all over the planet at the start of the extinction. In the 1990s, experts identified a massive buried crater near Chicxulub in Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula as the likely impact site.

“We wanted to determine the origin of this impact,” says Mario Fischer-Gudi, an isotope geochemist at the University of Cologne. To find out what this object was and where it came from, he and his colleagues took samples of K/Pg rocks from three sites and compared them with rocks from eight other impact sites from the past 3.5 billion years ago.

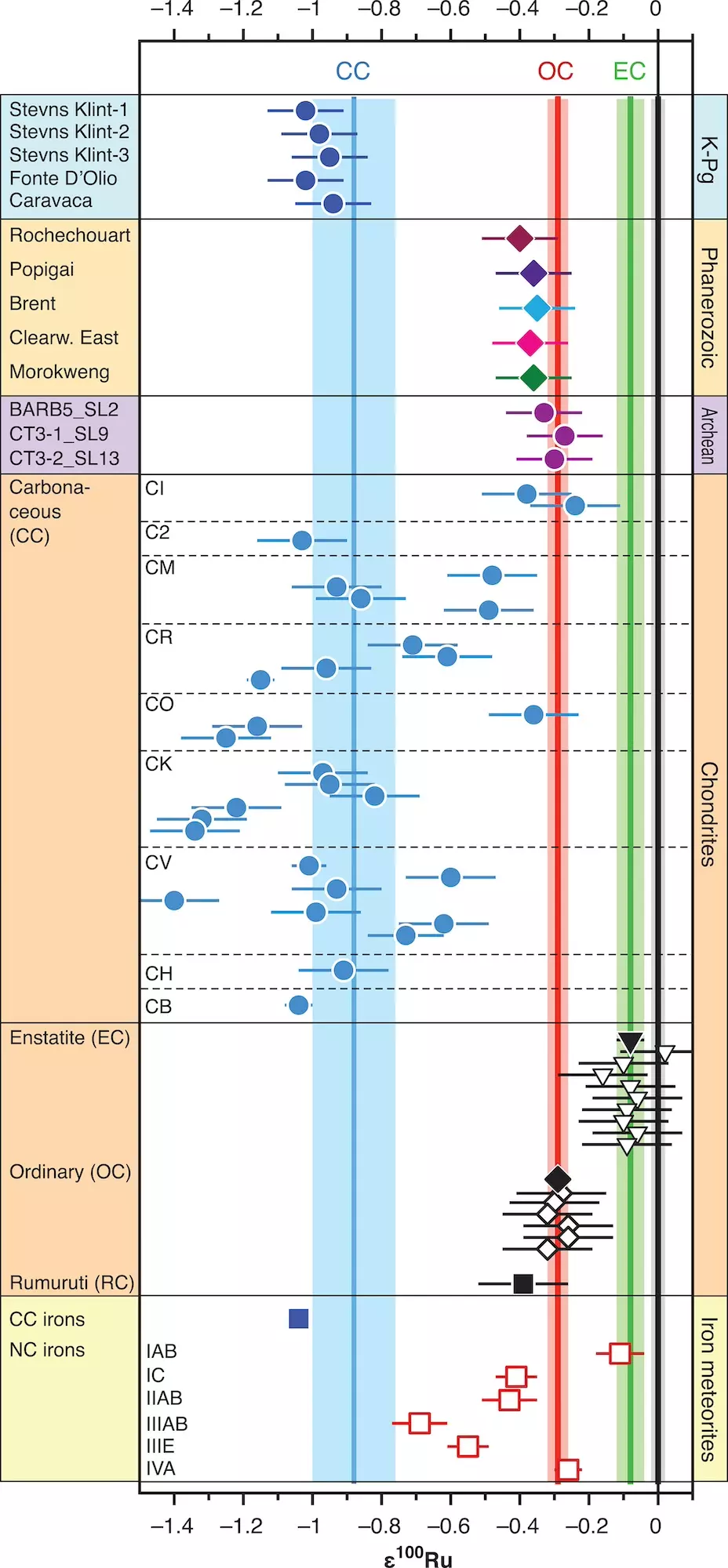

The team focused on ruthenium isotopes. According to Fisher-Goudy, the element is extremely rare in Earth rocks, so samples taken from the impact site provide important information about the impactor. There are seven stable isotopes of ruthenium, and different celestial bodies contain unique mixtures of them.

In particular, studying ruthenium isotopes could help researchers distinguish between asteroids that formed in the outer solar system—outside the orbit of Jupiter—and asteroids from the inner solar system. When the solar system formed from a molecular cloud about 4.5 billion years ago, the temperature in the inner region was too high for volatile chemicals like water to condense. As a result, asteroids that formed there were low in volatiles, but rich in silicate minerals. Asteroids that formed farther away became carbon-rich, meaning they had a lot of carbon and volatile chemicals. Ruthenium isotopes were unevenly distributed in the cloud, and this heterogeneity was preserved in the asteroids.

The Fisher-Judy team found that the ruthenium isotopes found in the Chicxulub crater matched well with carbonaceous asteroids from the outer solar system, but not with silicate asteroids from the inner solar system. Previous studies had also suggested that the impactor was a carbonaceous asteroid, says Sean Gulick, a geophysicist at the University of Texas. But the latest work shows the same thing in a really elegant way, in a different way.

The ruthenium isotopes also provide evidence against another hypothesis: that the Chicxulub impact was not caused by an asteroid, but by a comet. “The idea that it was a comet has been in the literature for a long time,” says William Bottke, a planetary scientist at the Southwest Research Institute. That hypothesis was recently revived by a controversial study published in 2021 that suggested the impact site was the result of a long-period comet that collapsed under the sun’s gravity.

However, according to Fischer-Jude, the ruthenium isotope data do not support the cometary theory, which Gulick also agrees with. He adds that the geochemical evidence from the Chicxulub crater has never been consistent with a cometary impact, and the latest study does a very good job of confirming that.

Buttke adds that the comet hypothesis is unlikely because of the dynamics of the solar system. “Large carbon-based asteroids are more likely to impact Earth than comets,” he says. In a 2021 paper, he and his colleagues argued that the impacting body likely came from the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter.

Based on their ruthenium isotopes, most of the other impacts the Fisher-Goudy group has studied originated in the inner solar system. The exception is the oldest impact, from 3.2 to 3.5 billion years ago, which looks a lot like what caused the Chicxulub crater. It’s possible that something strange happened in the asteroid belt at that time, like a large asteroid breaking apart in a location where pieces could easily have made their way to Earth, Bottke says.