A new study shows that more than half of Switzerland’s glaciers have disappeared in less than 100 years, and this year’s long, hot summer has accelerated melting. – Draws attention to the BBC scientific journal.

Glaciers are vital to Europe’s water supply. Now the alpine communities are worried about their future.

In Switzerland, at 3,000 meters above sea level, one would expect to see ice. But above the village of Les Diablerets, where the Glacier 3000 ski lifts operate, there is now a vast expanse of bare rock.

Two glaciers, the Tsanfleuron and the Scex Rouge, have already opened, revealing a land unseen for thousands of years. “We may be the first to walk here,” says Bernard Chanin, the company’s operator.

Mr. Chanin watches an attraction in Switzerland disappear before his eyes. Tourists can be seen from the Eiger to the Matterhorn to Mont Blanc. They too, until recently, could walk through miles of ancient blue glaciers.

Rocks, mud and puddles broke the ice. The change is dramatic. When they built this gondola 23 years ago, they had to go 7 meters into the ice. Now the ice has shrunk a lot.

Scientists have been watching shrinking glaciers in the Alps for years. A related study from the Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich and the Swiss Federal Landscape Office compared topographic images of glaciers from the 1930s to the past 10 years.

The findings are consistent with older evidence that Europe’s glaciers are shrinking and that there is a direct link between ice loss and global warming.

Ice caps are particularly sensitive to temperature changes, so when the Earth warms, glaciers detect them first and respond with melting.

Mauro Fischer, a glaciologist at the University of Bern, is responsible for monitoring the Tsanfleuron and Scex Rouge. He installs snow gauges every spring and checks them regularly during summer and fall. When she went for a medical exam in July, she was shocked.

The bars had completely melted from the ice and were lying on the ground. He says his ice measurements were farther than anything he’s measured since he began monitoring the glaciers. Perhaps three times the mass loss in one year than the average of the last ten years.

Melting brings with it danger. In the famous resort of Zermatt, the roads to the Matterhorn had to be closed because as the glaciers melt, the rocks once held together by the ice become unstable.

Richard Lehner, a Zermatt mountain guide like his father and grandfather before him, spent less time climbing this summer and more time repairing or rerouting dangerous roads. He remembers being able to walk through the Gorner Glacier. This is no longer possible.

The permafrost is melting on the mountains.

There are more gaps in the glaciers because there is not enough winter snow, which makes their work more difficult. More thought must be given to risk management.

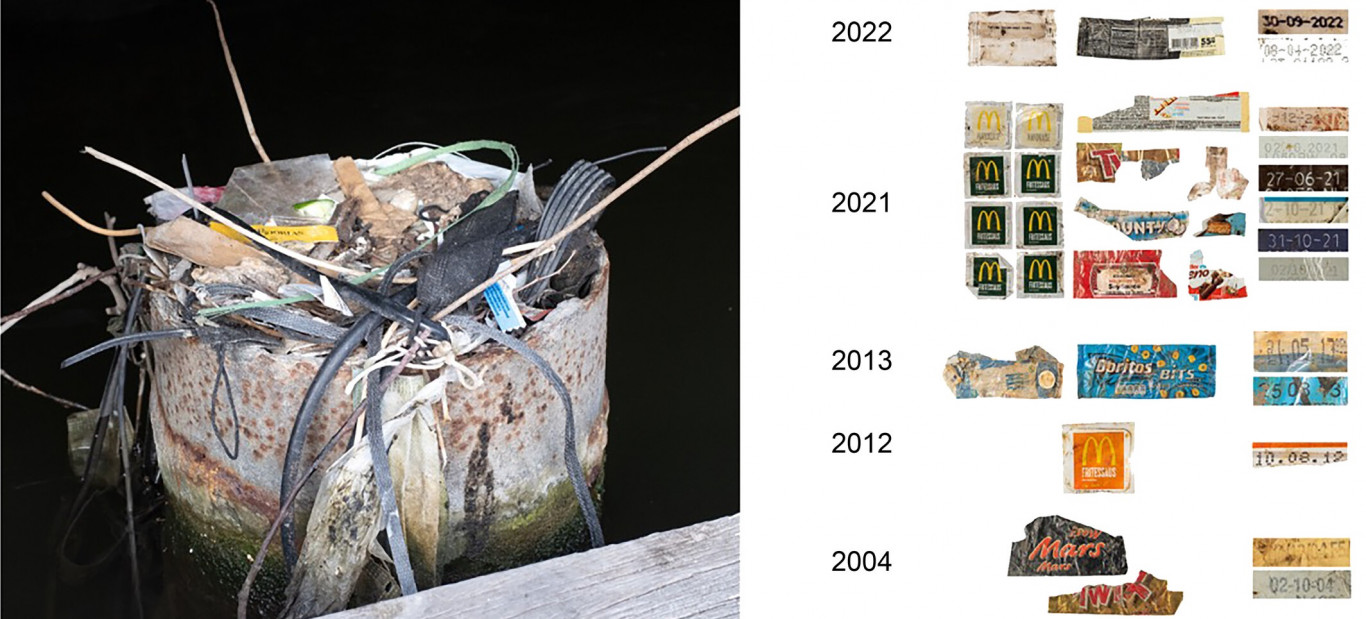

Melting glaciers also reveal ancient secrets. This summer, the wreckage of a 1968 plane crash emerged from the Aletsch Glacier. The bodies of climbers that had been missing for decades, perfectly preserved by the ice, were also discovered.

But the consequences of losing ice are much broader than harming local tourism or finding missing climbers.

Glaciers are often referred to as the water towers of Europe. They store winter snow and release it gently during summer, supplying rivers and crops in Europe with water and cooling nuclear power plants.

This summer, in Germany, the transportation of goods along the Rhine ceased because the water level was too low for heavily loaded barges. In Switzerland, dying fish was urgently saved from very shallow and very hot rivers. In France and Switzerland, the capacity of nuclear power plants had to be reduced due to limited cooling water.

This is a sign of things to come, says Samuel Nussbaumer of the World Glacier Monitoring Service.

He says current projections are that by the end of the century, the only remaining ice will be high in the mountains: “There will still be some ice above 3,500 meters in 100 years. So if that ice disappears, there won’t be any water left.”

At Glacier 3000, Bernhard Tchannen began wrapping some of the remaining ice with a protective cap to slow the melt. He says they can help melt it maybe at a slightly lower speed, but he doesn’t think they can stop it completely, at least not at that altitude.

In Zermatt, Richard Lehner’s grandparents hoped that the glaciers would not spread far into the valley and cover the pastures. In the 19th century, there was so much ice that poor Swiss communities cut bits of it and sold it to elegant Parisian hotels to keep the champagne cold.

(Source: BBC News: https://www.bbc.com/news)