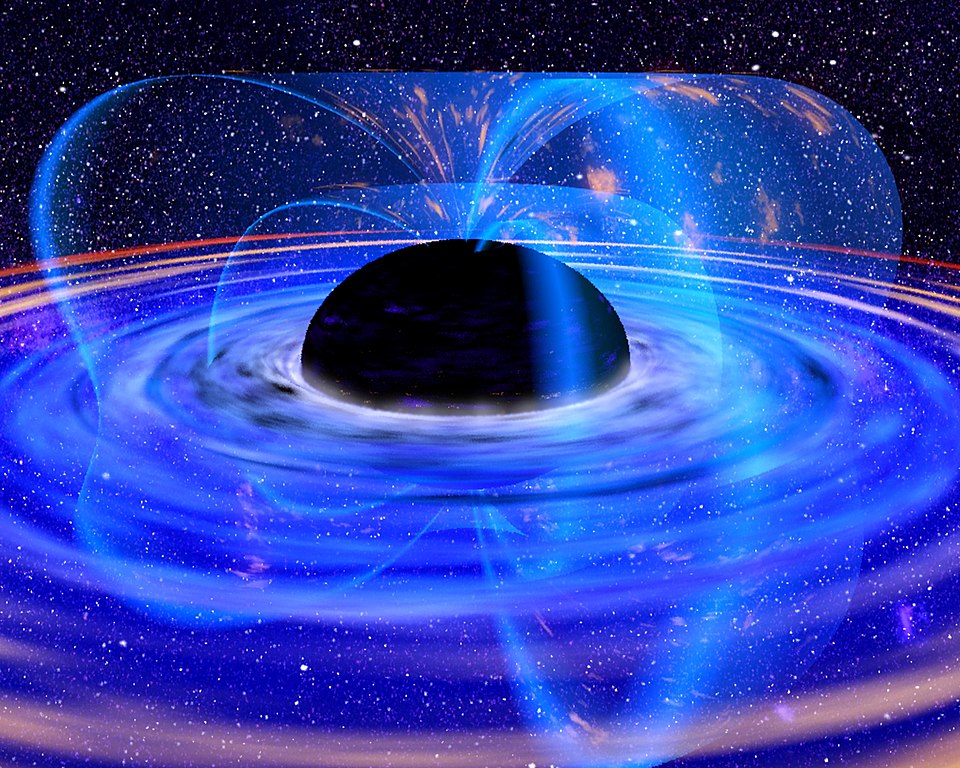

The first detection of a black hole hiccup leads to the surprising discovery of a second black hole orbiting it.

Scientists have discovered a supermassive black hole that “hiccups” every 8.5 days. A smaller black hole, which continues to collapse through its accretion disk, could be to blame, writes A Live sciences.

Astronomers have discovered the first known black hole whirlwind from a distant cosmic giant. The explosions suggest that swirling disks of matter and gas surrounding black holes may host larger cosmic objects than previously thought.

Mysterious hiccups

This black hole lives in the heart of a galaxy 800 million light-years from Earth, weighs about 50 million suns, and ejects chunks of gas into space once every 8.5 days before settling down again. These “hiccups” come from the black hole's accretion disk, which is a ring of extremely hot gas orbiting the object.

According to a new study published March 27 in the journal Science Advances, the matter comes from a second, smaller black hole in an inclined orbit, spewing out gas like a fast-flying bee releasing a cloud of pollen.

What does the accumulation disk hide?

The hiccup was “quite surprising,” Dheeraj Basham, the study's lead author from the Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research in Massachusetts, told Live Science. “We scratched our heads for months until theorists in the Czech Republic came forward and offered an explanation for a secondary black hole that seemed to explain all the properties of this system.”

The results suggest that accretion disks around black holes could host an amazing variety of cosmic objects, including black holes and other stars.

It is possible to misidentify black holes

“We thought we knew a lot about black holes, but this shows they are capable of much more,” Basham said in a statement. “If our model of the companion colliding with the accretion disk multiple times is correct, these hiccups could reveal a whole host of these extreme binaries.”

The researchers suspect that the massive gravity of the supermassive black hole will one day swallow its companion black hole in a merger, perhaps more than 10,000 years from now, “because the mass of the small black hole is much less than the mass of the main black hole,” Basham told Live Science. “The timeline for the merger is long.”

First visualization

Astronomers first noticed the monster black hole in December 2020, when the All Sky Automated Survey for SuperNovae (ASAS-SN) telescopes detected a long burst of light in its accretion disk.

During the survey, it spotted a flare that is now named ASASSN-20qc after it lit up a small pocket of the sky by a factor of 1,000. The flash lasted for four months, and was likely caused by a supermassive black hole tearing apart a nearby star.

Subsequent observations using the X-ray telescope aboard the International Space Station (ISS) allowed scientists to map the minute periodic dips of the feeding object in the X-ray data, similar to the way a planet passing in front of its host star briefly blocks light. These were the hiccups of the black hole.

What causes hiccups?

After discussing the process with their colleagues, the researchers determined that the black hole collapses every time the secondary black hole penetrates the accretion disc, ejecting more material than usual.

Although the secondary black hole is the smaller of the two in the system, it is by no means small. Scientists estimate that it is equivalent to 100 to 10 thousand days, a mass that classifies it as an average black hole. The huge difference between the masses of the two black holes, a difference of 5,000 times, makes the newly discovered binary among the most extreme in terms of mass percentage yet identified.

“It's a different beast,” Basham said in the statement. “It doesn't fit with anything we know about these systems.”

They want to know more about cosmic dualities

In the coming months, researchers will continue to monitor this system while also studying several other systems that also exhibit hiccups, Basham told Live Science.

If these black hole binaries present significant differences in mass, like the newly discovered binary, then ESA's newly launched telescope, the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA), will be able to detect them. “We expect to be busy modeling this new population over the next few years.”

You may also be interested in: