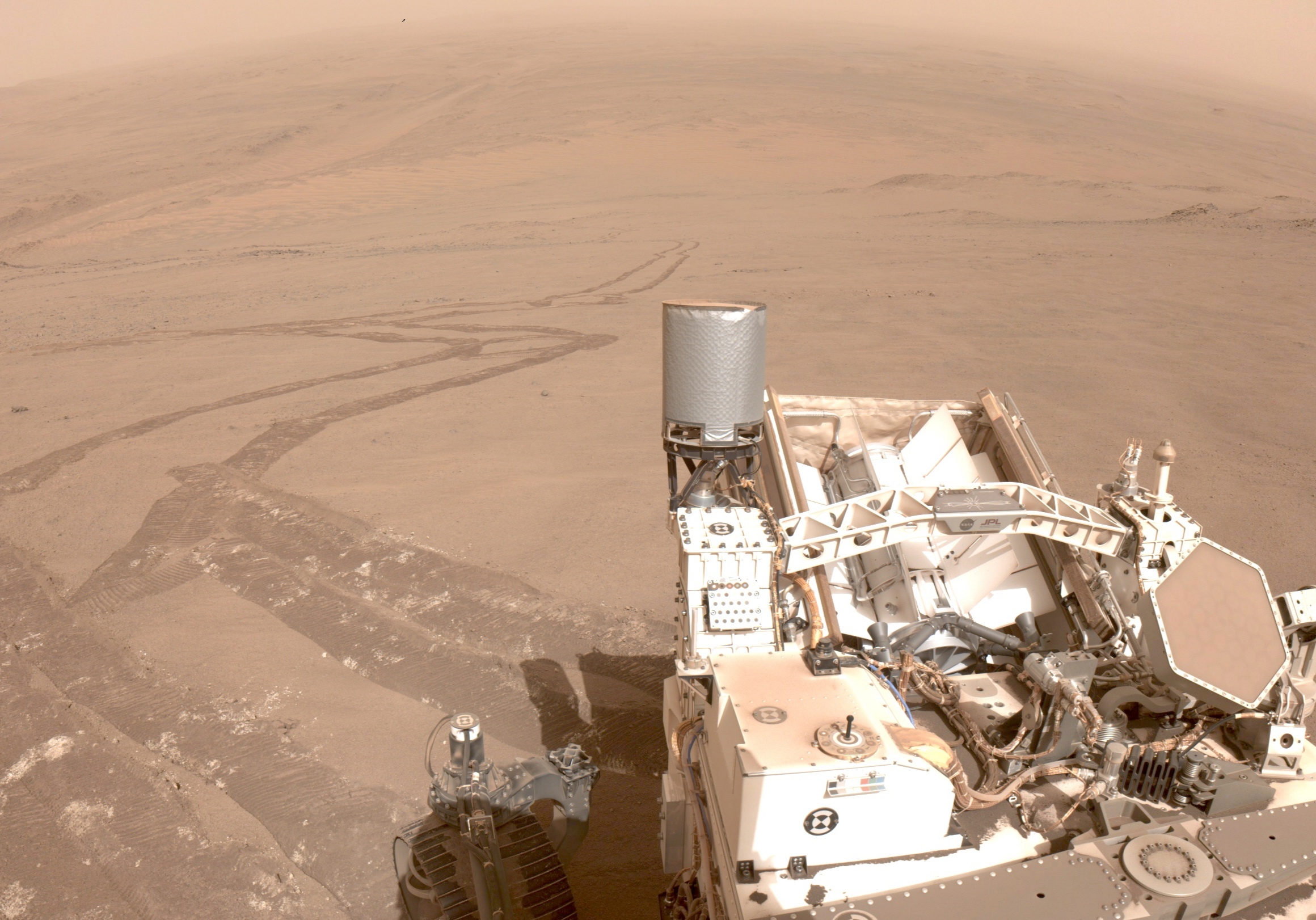

The composition of a meteorite found near Wedderburn, Australia, in 1951 is unlike anything studied to date.

Decades later, a mineral whose natural existence was previously unknown was found in the rare piece IFLS. This discovery could prove that the rock came from a planet that exploded in the early days of the solar system.

The Wedderburn meteorite contains proportionately more nickel (24 percent) than any meteorite ever seen. It also contains an unusually high concentration of carbon compared to other iron-nickel meteorites, although it is still much lower than other types.

This composition alone indicates that the material was once part of the planet’s core. Dr Stuart Mills, from Museums Victoria, said this was confirmed by some of the minerals found in it, which would require at least high pressure in the planet’s core to form without human help.

Although these rocks are rare, they exist because in the early days of the solar system, some partially formed planets collided with each other so hard that they shattered, scattering pieces of their cores throughout the inner solar system. These elements, like more common meteorites of less exotic origin, wandered through space for 4.5 billion years before falling to Earth.

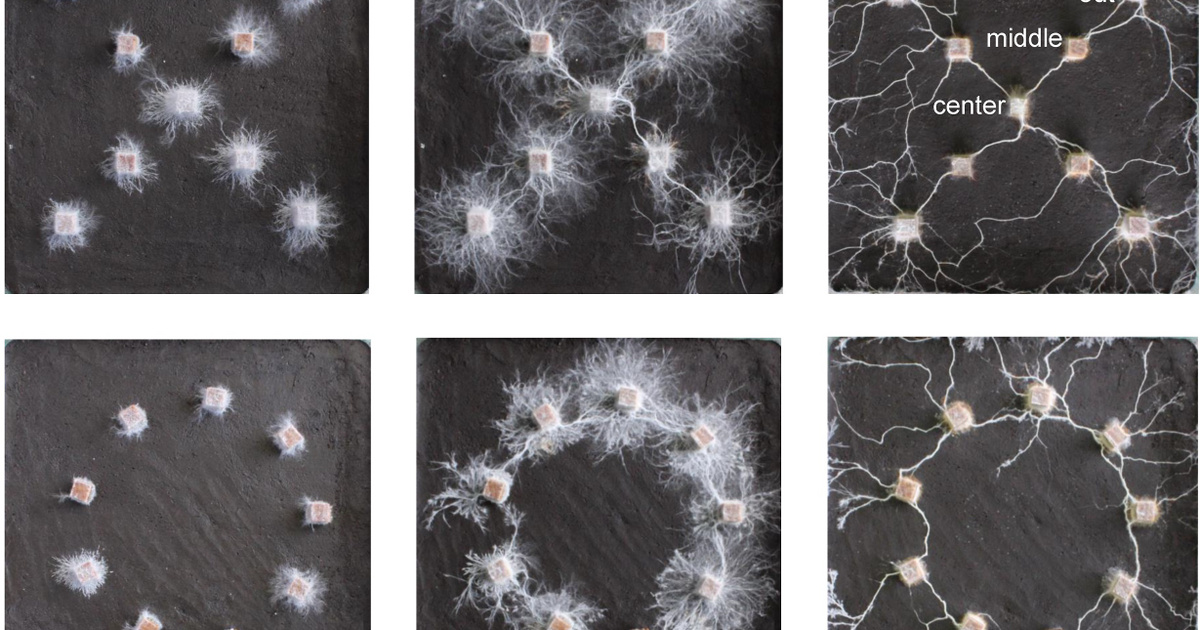

Planetary scientists now want to know why the Wedderburn meteorite contains more nickel and carbon than its peers, and what that tells us about the planet it came from. Dr. Chi Ma, an employee of the Caltech Research Institute, raised the stakes by finding iron carbide with the formula Fe5C2, with a distinctive structure, in the meteorite’s core.

The new mineral was named Edscotite in honor of meteorite expert Professor Ed Scott, whose doctoral thesis was on the Wedderburn meteorite.

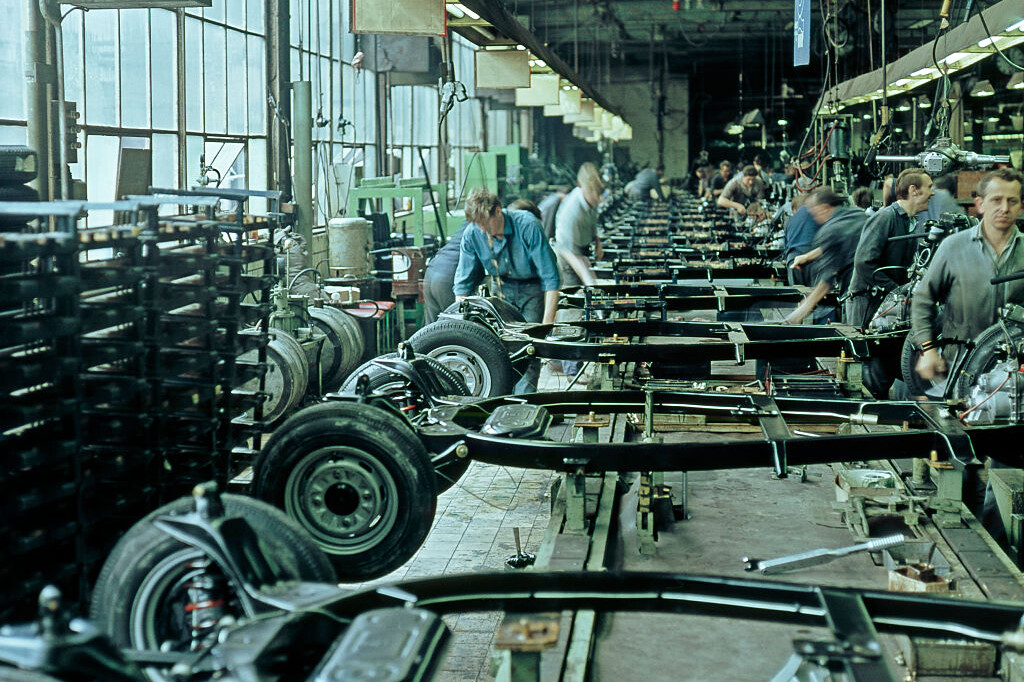

Until now, edscotite was only known as a step in the steelmaking process. By tradition, minerals are only named when they are found in nature, while these elements are only produced artificially, and are referred to by their formula – which is why, although scientists know of the substance’s existence, it has only now been given a name.

Meanwhile, Chinese scientists recently investigated whether nanoparticles of the same material could also be used to monitor tumors. The molecules bind to cancer cells and make them visible to MRI and other scanning machines, making them easier to target during treatment.

This might also be interesting: