We’ve only known for 150 years about the mysterious and small group of egg-laying mammals: Scottish zoologist William Caldwell was commissioned and supported in 1883 to prove that these animals lay eggs when they travel to Australia. Proof samples collected at that time were recently discovered in the museum’s repositories. By establishing the existence of egg-laying mammals, changing scientific thinking, the discovery supported the theory of evolution.

Private specimens from the collection were not included in the museum’s catalog at the time, so collectors were not at all aware of their existence. I recently came across Jack Ashby, the museum’s vice president, when he was looking for information about a new book on Australian mammals.

Anteaters from Caldwell’s group

Source: University of Cambridge / Jacqueline Gargett

“It’s one thing to read the nineteenth-century proclamation that ants and duck-billed mammals mated eggs,” Ashby said, “but it is impressive to preserve specimens that link the present to the moment when they were discovered some 150 years ago.” Relying on his museology expertise, he had already suspected that Caldwell’s collection could be somewhere here in the Cambridge Museum. They were also found three months later, and Ashby demonstrated that they had indeed found samples from Caldwell’s group.

Europeans did not encounter egg-laying mammals until 1790, until then they believed that every mammal was a living parent. The existence of egg-laying mammals was one of the biggest questions in zoology in the nineteenth century, and there was scientific debate about it because modern experts could not accept that a group of animals could mutate, as this would support evolution. Since reptiles lay eggs, humans simply ruled out the possibility of mammals reproducing in this way, which seemed like a “return” to an inferior form of life, according to contemporary perceptions.

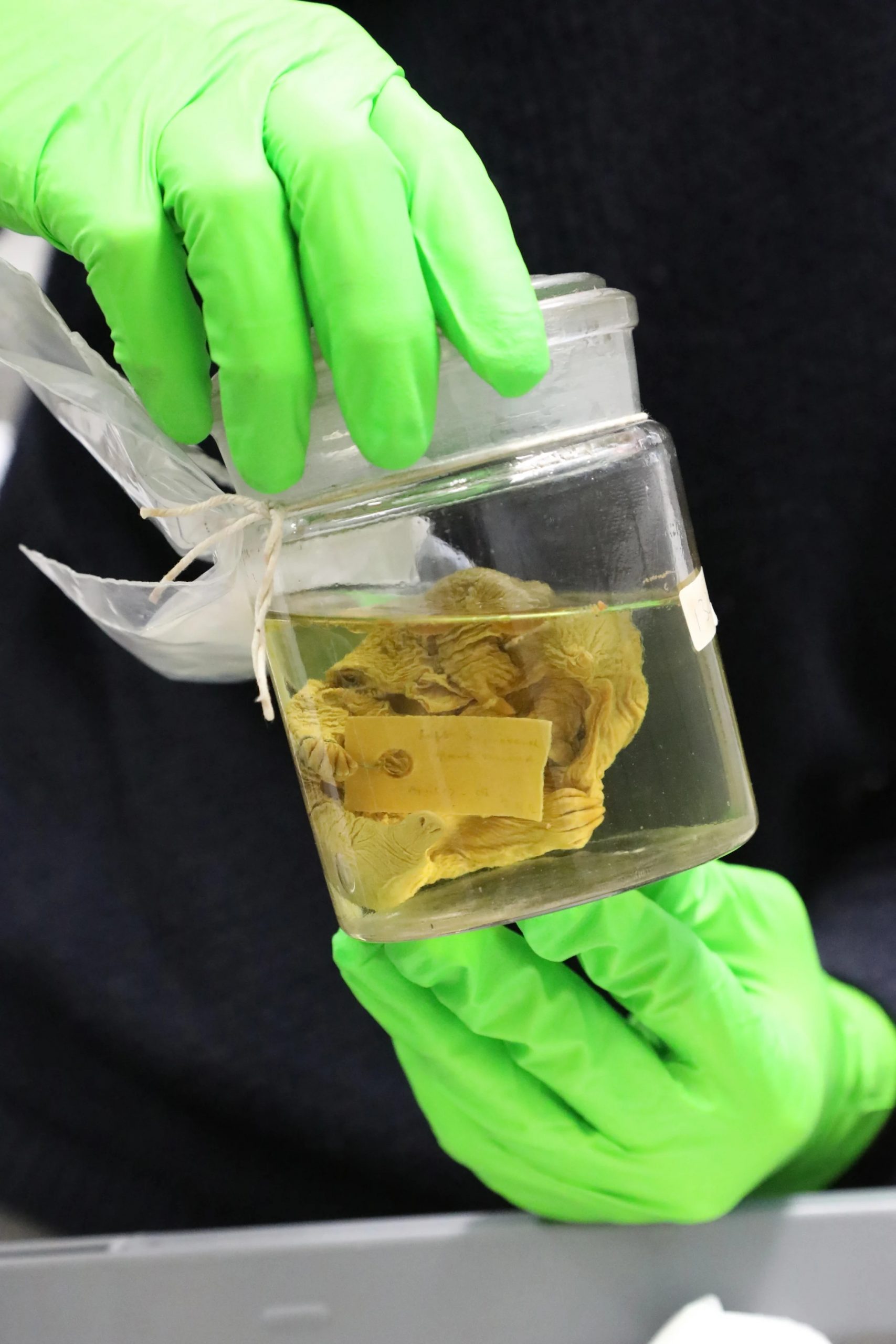

Baby anteater, also presumably from Caldwell’s group.

Source: University of Cambridge / Jacqueline Gargett

Rediscovered specimens include anteaters, duckbill mammals, and marsupials, at various stages of their development, from fertilized egg to pre-pubescent. Caldwell was the first to collect samples of each animal’s complete life stages, but not all of the pieces he collected are currently in the museum.

For 85 years, Europeans have been trying to find evidence of mammals laying eggs, but “rumours” like the sayings of the Australian aborigines were not credible to them. In 1883, with significant financial support from the University of Cambridge, the Royal Society, and the British government, Caldwell set out for Australia to solve this long-held mystery. In one year, he compiled a collection of about 1,400 specimens, with the help of the natives, and in 1884 they found an anthill with fresh eggs in his purse, and then a duckbill mammal already containing an egg in its nest. He was about to put a second one. These were the clues Caldwell was looking for, and he immediately published the news of his discovery to the world. The scientific community has finally acknowledged the existence of laying mammals now that a European scientist has seen and proven it himself.

Duckbill preparation of mammals from the museum.

Source: Cambridge University

Australia’s fauna over the past 200 years has been considered in disdain for the contemptuous and inferior observations of scientists. And the use of language to this day determines how we think about these creatures, and also undermines conservation efforts. “Duck-billed mammals and ant lizards are not exotic and primitive animals, as we have read in many ancient records, they are just as advanced as anything else. It’s just that they never stop laying eggs. I think they are wonderful and valuable!” Ashby explained.

The anteater has an outer covering that resembles thorns and can live all over Australia, from snow-capped mountains to the driest deserts. Duckbill mammals are the only mammals capable of sensing electricity and are one of the few mammals capable of producing venom. When the first preparations were brought to Europe, people thought they were dealing with fake products that were sewn together from several different animals.

Both animals have characteristics that 19th century scholars thought might only be characteristic of birds, reptiles, and mammals, and not of the same animal. This is why their existence has become a central issue in discussions of evolution.