When we hit a busy intersection with our car, we probably pay less attention to our current situation than where we will be in a few moments. This makes sense, since we should care about our future situation, not the current one, if we want to know exactly when we reach an intersection and whether we need to slow down, or even stop, to avoid hitting a car, cyclist or pedestrian crossing our path.

Neuroscientists at the University of California, Berkeley, suggest that this ability to focus on where we’re headed in the coming moments, rather than where we are now, is a key component of the mammalian brain’s built-in locomotion unit. A recent issue of Science magazine. The researchers used wireless transmitters to track the brain activity of the Egyptian fruit bats while the animals zigzagged through a journey that was new to them.

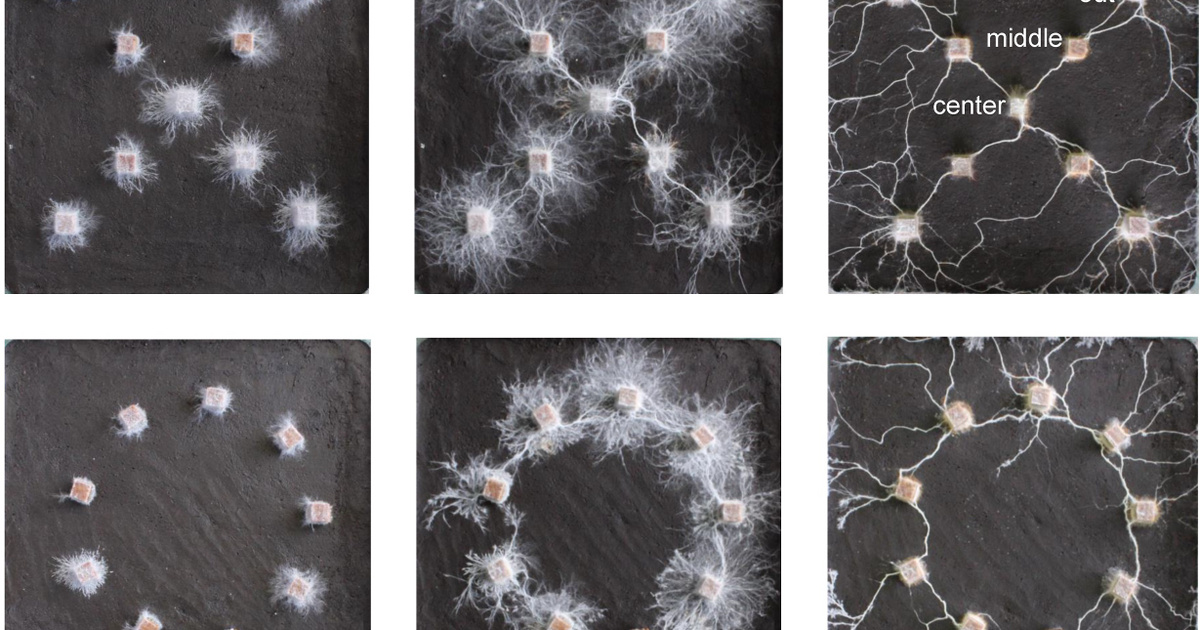

When the bats’ tracks were compared to the neural activity that was read, they observed that the bat brain’s “local cells” — special neurons that encode the animal’s spatial location — activate in a pattern closely related to their proximity. future position than it is now.

explained Nicholas Dotson, a postdoctoral fellow at Berkeley, and lead author of the article. The answer is that nerve activity is more effective in representing the future situation. Thus, the observed brain region does not or does not represent the current state of the bat in the first place, but rather is trying to determine the full expected trajectory.”

Location cells in a region of the brain called the hippocampus form a type of GPS innate in many terrestrial vertebrates, including humans, as part of a collaborative network. When an animal’s new environment is discovered, different local cells are activated in different places, creating an internal map of the region in the brain, which can then be stored and retrieved.

“If someone follows the nerve activity in the hippocampus as they walk around the room, they can infer from the pattern of activity where I could be now,” Dotson explained. The Nobel Prize in Medicine was awarded in 2014 for the discovery of local cells in the rodent brain, but the founding class Most experiments were conducted as early as the 1970s and 1980s, but there are still many open questions about how this area of the brain works with rapid movement and how non-present situations work. Which situations, in which. She is currently unoccupied at the moment.

“Because the hippocampus is known to play a role in navigation, quite a few studies have looked at neural coding in this region of the brain, looking for answers to the question of how brain activity here depicts what is expected in the future and what happened in the past,” he said. Michael Yartsev, assistant professor of bioengineering for neurobiology at Berkeley. The experiments also sought to clarify whether the hippocampus could show activity that represented a remote location in space rather than our current location.

However, experimental work so far has failed to convincingly address these issues, notes Yartsev, adding that one possible reason for this is that it was conducted with relatively slow-moving animals, such as mice, which are only 5 to 10 centimeters long. per second in a laboratory cage. However, if we observed the activity of individual neurons as a function of spatial location, we would not see huge changes as a result of a few centimeters of displacement.

On the other hand, bats are lightning-fast aerial acrobats. “Bats are very, very fast,” Yartsev stressed.They also fly at lab speeds of 30-50 km/h, which is a huge advantage for the current experience. In the same split second, while the rat is moving a few inches forward, the bat is flying a meter.”

Experience

For the experiments, the bats’ brain activity was recorded by Yartsev and Dotson radios while the animals were meandering in a specially designed chamber. The room was equipped with cameras that accurately tracked the path of the bats at every moment. In some experiments, humans encouraged bats to traverse the entire 3-D volume of a chamber while recording their location and brain activity. In other experiments, the bats were in the same room, but robotic feeders were placed at different points, which encouraged the animals to explore space.

When Yartsev and Dotson compared the timing of neuronal activity to a bat’s flight path, they found that comparing a bat’s location to time — that is, neural activity compared to a few hundred milliseconds, even a second later — compares it to location. between the pattern of neural activity and spatial location. “If one looks at only the raw data, one might conclude that some neurons in the hippocampus do not encode spatial information at all because there is no correlation between activity visible at time t = 0 and spatial location,” Yartsev said. “However, if we compare neuron activity to spatial location after one second, we suddenly get an incredibly accurate correlation.”

The results show that local cell activity does not represent a single current state, but rather a line of action that covers the near future—and possibly the recent past.

“We can imagine walking down the hallway and thinking about where we were just and where we will be now. What does this look like on the level of brain activity? Dotson asks.Our results indicate that the brains of bats represent not only their current position during flight, but also their position along the entire line of motion.”

Although the location cells themselves and basic components of the entire navigation system have been identified in a number of different mammals, it is not clear whether the ability to display path-per-second is unique to bats famous for their fast flight or shared by others. Ocean. So the discovery raises a number of other exciting questions, including how we humans process movement in our brains in space and time.

Since the hippocampus is implicated in a variety of neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease with spatial cognition and memory impairment, discovering the underlying neuronal processes here could also contribute to a better understanding of disorders in disease and may contribute to more effective therapies.

“Perhaps creatures moving on the ground do not have to look into the future as far as bats do, but even us, humans, can depend on the situation,” Yartsev stressed. “If we were only walking, we would probably know enough to anticipate it right in front of our noses. However, if we were actually driving a car, we have to plan a few meters in advance, because we are going at high speeds. Now that we know that there is some kind of neural representation of future spatial situations in Bats, we can go ahead and ask the question: What are the common elements of this system in different animals? And of course: in what way and to what extent do we humans have this ability? “